- Home

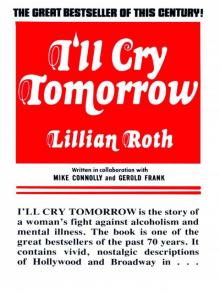

- Roth, Lillian;

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Page 3

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Read online

Page 3

But when we returned to New York—and Dad—there were only arguments after the affectionate greetings of the first few hours. For added to Dad’s uncontrollable temper was his jealousy.

“Did Mother ever leave you alone between shows,” he would ask, taking me aside. “Was she with you all the time?”

I knew Mother went nowhere. Time and again I awakened to see her sitting beside us, reading by the little table light, reluctant to slip into bed with us because of what terrors the night might hold. She feared the darkness, and often in a hotel she saw—or thought she saw —a man peeking over our transom.

Once she was sure of it. She woke us, frantically. “Babies—babies—get up, hurry up, there’s a man after us!”

She could hardly dress Ann in her panic. My fingers were all thumbs as I tried to button my clothes. I was sick with the terror on my mother’s face. I went into a cold sweat My heart pounded in my ears. I was sure something monstrous was breathing in the room.

Then we were rushing out and down the stairs into the dimly lit lobby and Mother was screaming at the lone desk clerk—not knowing but that he might have been the man himself. Then we were running through the dark streets, my mother shrieking for help, until we found another place to spend the night. But there was no more sleep.

Once I woke to find her brushing things off us. “What are you doing, Mommy?” I asked sleepily. “Get out of bed,” she said excitedly. “It’s full of bedbugs!” Minutes later she had us dressed and furiously rushed us out of the hotel.

The streets of the small towns were always deserted late at night when we walked from the theatre to our hotel. What might not be lurking behind every tree, every shadow? Sometimes we heard footsteps behind us. We hurried, and the footsteps quickened, and I was limp with fear until we reached the bright lights of the hotel.

Back in New York the arguments grew more bitter. I was in an agony of shame when my father began his accusations, sometimes behind the locked door of their bedroom. I became hot and cold, I tore at my nails. How could I face people who heard them screaming at each other?

Once, a quarrel broke out between them in the kitchen. They began to struggle, and something exploded in me. “Stop it!” I screamed hysterically. “Stop it, I can’t stand it!” I grabbed my glass piggy bank and threw it with all my might between them, trying to separate them. It crashed against the wall. My parents, startled, turned to me, and a moment later I was in Katie’s arms, and we were both sobbing.

Dad was all remorse. He took a quick drink and then another. “How could I do this to my Katie! To my Lilly!” He began to cry. “They can string me up from a tree if I ever lay a hand on you again, Katie!”

My mother could only shake her head. “You and your crocodile tears.” She wept, and took me into the bedroom, where Ann slept, undisturbed.

On another occasion, at a gathering, a handsome man engaged Katie in a long, bantering conversation. Dad’s face grew pale. He was in an ugly mood when we came home. For a while he drank silently.

Then—”Will you be good enough to tell me—” he began, grinding his teeth as he always did when he was about to explode.

“Arthur. The children…”

Praying they would not fight, I tiptoed to bed. But suddenly I heard piercing screams. I leaped out of bed and ran into the kitchen. My mother lay on the floor, blood trickling from the corners of her mouth, her eyes puffed, her face bruised. She was rolling wildly back and forth, screaming uncontrollably, catching her breath, then sobbing and screaming again.

My father, a long red gash on his face, was in his bathrobe, slumped in a chair, his eyes glassy, a bottle beside him. He moaned to himself, “Oh my God, Lillian what did I do?”

He rose, as if to go to my mother, but she shrieked, “Don’t come near me—don’t touch me!” He fell back into his chair.

I pulled her to a couch and cradled her head in my lap, while my father repeated dully, “Do something, Lillian, do something.” I was sick to my stomach with fear and horror, and with a compassion I could not put into words. My mother moaned and wept, and my father slumped in his chair, looking at nothing.

I spent the remainder of the night running between the living room, where my mother lay weeping, and the kitchen, where my father sat staring at the wall, and drinking. Katie fell asleep, finally, but I was in the kitchen every few minutes, tugging at my father’s arm, shaking him, imploring him, “Please don’t fall asleep, Daddy, please, please!” I did not know what I feared, but I knew he had to remain awake, he had to remain awake.

For years afterward there were many nights that I could not fall asleep until daylight came through my bedroom window.

CHAPTER III

I WAS TWELVE when Katie, seeking new stage personalities for me to impersonate, took me to see Lenore Ulric in “Kiki.” I fell in love with her. What fire and passion in her performance! Oh, I thought, if only I could be like her!

At Katie’s suggestion I took enough courage to write her a note, and she invited me to her home. I trembled as I rang the bell.

Miss Ulric herself opened the door. I was overwhelmed for a moment by this exotic, vibrant personality, dressed in beautiful black satin pajamas.

“Oh, Miss Ulric, I’m Lillian Roth who wrote you about impersonating you,” I burst out.

“Good heavens,” were her first words. “You look enough like me to be my twin. A little twin!”

“Oh, thank you, Miss Ulric,” I said breathlessly. “That’s what many people tell me, and you’re my idol!”

She put her arms around me and kissed me. Then, to her maid, “Bring in some cake and milk.” She turned to me. Was there any scene in the play I would like to do?

I told her it was the scene in which Kiki, brandishing a stiletto, turns on the society lady who seeks to steal her lover and cries, “I am a Corsican! My father is Corsican! My mother is Corsican! And when we are angry, we know how to use the knife. We do it like this—”

I seized the cake knife and launched into her scene.

“Wonderful! Wonderful!” she applauded. “Very, very good. But you must lower your voice deep into your throat, and you must run your hand wildly through your hair” She did the scene several times for me, and then later said, “If you feel you haven’t the characterization just right, come back.”

I added Helen Mencken, Judith Anderson and Jeanne Eagels to my repertoire. How electric Jeanne Eagels was in “Rain,” how alive—every move, every turn, a picture. Oh, I thought, to be a dramatic actress! What was vaudeville compared to the legitimate stage—a full three hour show in which you felt so deeply, in which you reached out and touched people’s souls.

Suddenly Dad was in the big money. While we were on tour, he had gotten a job as head salesman for a Fifth Avenue clothier and earned as much as $300 a week. He used much of it, plus some of our money, for “investments.” He was always going to hit on something that would bring us a fortune overnight. Then, he promised, he would buy us everything we wanted, including the house and garden.

Now that he was doing well, Katie was finally able to realize one of her dreams—a private school for us. She decided to take us out of show business for a year, so that I could attend Clark School of Concentration, a fashionable cram school. My one term here, as it turned out, completed my formal education.

I entered Clark like the little lady Katie wanted me to be. She bought me a $1,000 wardrobe. Overnight, my socks and oxfords were discarded along with my childhood. I had been skipped several grades at the Professional School, and was only thirteen when I received my diploma. Now, at Clark, I found my classmates were three and four years older than I. On the threshold of fourteen, I was a grownup without even having known what it was to be a child.

Today when I come upon John Held, Jr’s drawings of flappers in the fabulous 20’s, I see myself. Silk blouse, dangerously short skirt, rolled stockings, red garters with bells, long fluffy bob (after Ulric), and a vanity case piled high with makeup and cigarettes. I did

n’t smoke. But the advertisement read, “Be nonchalant Light a Murad.” And I wanted to be nonchalant, I wanted to be sophisticated.

But I knew the picture I saw of myself was wrong. For I was anything but nonchalant. I was impatient, impatient for I knew not what, driven by an energy I could not control. I seemed to have a clock ticking in me faster than any one else’s: time itself could not move swiftly enough. I was full of anxieties—whether people liked me, whether my acting was adequate, whether I was as good as I should be.

Often I discussed this with my best friend, Minna Gellert She was a year older, a shy girl who wrote poetry. Until I met her, at 13, I had not even had a close friend. I envied the serene atmosphere of her home, and I envied her poetic ability. That, I thought, was real talent. And although I was busy with rehearsals, dancing, music, acrobatics, I felt they were mundane accomplishments. I was discontented, tormented by an inner compulsion to be the prettiest, the best, the greatest. When things became too hectic for me—when it seemed I wanted to leap out of my skin, stop all the clocks, loosen all the bonds—I would confide in Minna. “Why am I so tense?” I would ask, despairingly. “Why can’t I slow down!”

“Lillian,” she would reply in her slow, calm way. “It’s only that you have all that creative ability in you. Just give yourself a chance. You haven’t found yourself yet.” And so she soothed me.

The classmate I was most interested in at Clark was Leo Fox, a tall, dark, curly-haired boy of 17 I concentrated the Ulric look on him in history class one day, and soon he was taking me for ice-cream sodas and Saturday night movies. He was my first flame. The girls tagged him “Lillian’s sheik.” Another schoolmate was Carl Laemmle, Jr., whose father was president of Universal Pictures. He called for me in a chauffeur-driven Stutz Bearcat, the last word in rakish automobiles, and we talked about the movies of tomorrow. On our first date he put his arm around me and in a warm, confidential voice, murmured, “You know, Lillian, some day I’ll be a big Hollywood producer.” “Oh, yes,” I said, deftly extricating myself. “My father always says, ‘Talent will out.’” Junior took the hint.

Besides, hadn’t a critic in the New York World written: “Thirteen year old Lillian Roth is a real find. She has a dramatic sense unusual in one so young, a dramatic intensity which bids fair to see her go far on the road to stardom.”

Toward the end of my school term, Willie Howard, the comedian, saw me at a benefit performance. He took Katie aside. “She’s too big to be doing kid stuff,” he said. “Why don’t you try her out for a show?”

He jotted something down on his calling card. “Here,” he said, “Tell Lillian to take this to Jake Shubert and say Willie Howard sent her.”

The following Monday, having cut classes, I was ushered into Mr. Shubert’s presence. After all, Willie Howard had written: “Dear J. J. This is Lillian Roth. Star material.”

Mr. Shubert looked on either side of me, then caught me in a swift, sidewise glance—a habit of his—and asked softly, “What can you do?”

“I’m a dramatic actress,” I announced.

“Sorry, little girl.” He turned away. “We’re casting for ‘Artists and Models.’ I need singers.”

“I sing, too,” I said, my fingers crossed.

“All right,” he said, after a moment “Come back at nine o’clock. I’ll hear you.”

At the appointed hour I found nearly 200 persons—the entire cast—onstage. Was I to audition before all of them? Mr. Shubert walked into the empty theatre. “Go ahead,” he flung over his shoulder. “Sing!”

Standing in the midst of the cast, and still in hat and coat, I sang “Red Hot Momma.” Mr. Shubert was somewhere out in the darkness, but I couldn’t see him. Well, I thought with a sinking feeling, I guess Katie was right about my singing. I began to leave the stage.

“Where are you going?” came his voice. “Let’s have another number.”

I tossed off my hat and coat and gave everything to “Hot Tamale Mollie.”

Silence. Then Mr. Shubert’s voice rumbled, “How old are you?”

“I’m going on fifteen.”

“Wait around. I’ll talk to you later.”

After the auditions he asked if I knew the regulations of the Gerry Society, which looked after juveniles in the theatre. I was too young to sing or dance in New York. But, he said, “I’ll put you in my Chicago company. We can change your age there. From now on, you’re 18, Lillian.”

I ran all the way home and barged into our apartment “Mom,” I shouted, “meet your 18-year-old singing soubrette—the star of ‘Artists and Models!’”

My mother almost fell off her chair.

I was not, of course, the star of “Artists and Models,” but I was a singer—and being paid for it. The joy, however, was not quite what I expected. For Mr. Shubert might change my age, but I was still 14—and “Artists and Models” shocked me. It introduced me to nudity—and to headaches, the kind of headaches I suffered later whenever I couldn’t cope with a situation. I shared a hot, sticky cellar dressing room with 20 showgirls who posed in the finale uncovered from the waist up. I had never undressed before another girl, and the nonchalance with which they strolled about backstage with hardly a stitch on, and the equal near-nudity of the chorus boys, who called each other “Betty” and “Mildred,” distressed me.

When I complained of headaches, Marie Stoddard, a kindly woman who played character parts in the show, took me in hand. “Christian Science can help you,” she said. She gave me a copy of Mary Baker Eddy’s Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, and a small Bible, and showed me chapters in both to read every night.

“Lillian,” she said to me one afternoon, when my head seemed gripped in a vise and I had to hold back the tears, “your pain is only a dream. Try to understand that, dear. You are part of God’s mind, and God’s mind sees no evil and feels no evil.” She sat beside my cot and was so gentle and persuasive that often my headaches seemed to vanish. She spoke constantly of Jesus Christ. “Many of the Jewish faith read Christian Science,” she assured me. “It doesn’t interfere with their creed. It merely tries to prove that we are all part of one mind—the mind of God.”

As I once tried Dr. Coué for my hands, I now invoked Christian Science for my headaches, wandering about repeating, “I have no headache…My headache isn’t real…”

The chorus boys liked me and used to protest to Katie that she wasn’t letting me grow up. “Why don’t you get her out of those skirts and blouses? Her figure is developing beautifully.” They showed me how to bead my eyelashes and even whipped up a sophisticated dress for me. “Never laugh at the way they act or talk,” Katie warned me. “They’re born that way. They have a marvellous sense of humor and they can be wonderful company.”

Since there wasn’t anyone my age in the show and I was lonely, it wasn’t surprising that Katie allowed me to go to a company party one Saturday night. Immediately after the show the full company piled into half-a-dozen automobiles. I was taken by the stage manager, who promised he’d bring me back safe and sound. We drove for miles until we reached a huge barn-like house near River Forest, which had been rented for the occasion.

Once inside, I gaped. Were these men—or women? They wore hats pulled down to one side, carried canes, wore monocles, cigarettes dangled from their lips; they wore stiff collars and ties, tight, narrow skirts, low-heeled shoes, three quarter coats. Then I got it. These were chorus boys in reverse! But boys were there, too. The girls called other girls “Bob” and “Johnny,” and the boys whistled and shrieked at each other. Nearly everyone got drunk. For most of the party I sat in a corner, wide-eyed, drinking sasparilla and taking it all in.

A boy wiggled himself into a beaded outfit and did the shimmy. A girl danced nude on a table. Women danced wildly with other women; then every few minutes a pair would disappear to another part of the barn, out of sight. I felt a little ill. Vaguely I knew there was something dark and wrong here, but nothing quite crystallized in my mind.

> I asked my escort, “What are they doing? Where are they going together?”

He laughed, and shrugged it off, and the mystery remained.

When I came home Katie asked sleepily, “Did you enjoy yourself, baby?”

“Fair, Mom,” I said. “Nobody asked me to dance.”

I didn’t know how to begin to tell her.

Shortly after this Katie took me out of the show, pleading illness. My headaches had become worse, and the best the doctors could advise, finding nothing organically wrong, was a change of scene. It was just as well, Katie said. “Artists and Models” was no place for a girl my age.

We returned to New York.

“All you need, darling,” said Katie, “is a good rest.” And then she placed balm upon my head. “You’ve proved yourself a singer, you dance beautifully, you act well— you’re going to become a big musical comedy star!”

CHAPTER IV

IF ANYONE typified the years in which I was coming to womanhood, it was Texas Guinan. Those were the years of Harding and Coolidge, of marathon dances and the Charleston, of Peaches Browning and Rudolph Valentino and Lucky Lindy.

I had just finished a Keith tour in which I had introduced “How Many Times,” “When the Red Red Robin Comes Bob Bob Bobbin’ Along” and “Ain’t She Sweet,” when two of Texas’ backers heard me rehearsing at Irving Berlin’s offices. They were putting up the money to bring her famous nightclub review, “Texas Guinan’s Padlocks of 1927,” to Broadway. They asked me to audition for her.

I was sixteen and shy—I thought I knew all the answers (after all, I had been in “Artists and Models”)—but I was still a little girl who played “Spin the Bottle” at parties and kept company with Leo Fox when his parents allowed him to go out with a wicked actress like myself. La Guinan, raucous and uninhibited, was something special for me.

I'll Cry Tomorrrow

I'll Cry Tomorrrow