- Home

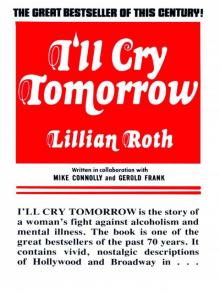

- Roth, Lillian;

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Page 2

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Read online

Page 2

She cried out with horror. “Oh, my poor baby! What have I done!” She picked me up, and almost beside herself, began to cuddle and kiss me. My left eye was beginning to puff. “Oh, God, look what I’ve done!” And then, “Oh, my God, what will your father do when he finds out!”

She was rocking me in her arms, both of us crying. I smothered my mother’s face with kisses. “Don’t worry, Mommy,” I managed to get out. “We can tell him I fell against this lamppost, can’t we?” I pointed to one conveniently near.

“Oh, he won’t believe it,” she said miserably.

“Yes, he will. I could have slipped …”

We memorized our story on the way home. My father was in the kitchen when we arrived. When he saw me he uttered an exclamation. “Come over here, Lillian! Let me look at that eye!”

I walked over slowly, my fingers crossed behind my back so that I could tell a fib without being a bad girl.

“How did this happen?”

“I slipped and fell against a lamppost, Daddy. It was very icy—”

My father looked up suspiciously at Katie, then back at me.

“Is that the truth?” he demanded.

“Yes it is, Daddy,” I said stoutly. “And I can show you the place, too.”

He surely knew then that I could not be telling the truth, but he only grumbled as Katie, maintaining a discreet silence, wrung out a cloth in water and held it tenderly to my eye.

I missed the part in “The Bluebird,” but Ann and I played Constance and Norma Talmadge as children; then I was Evelyn Nesbit as a child; then we were cast to play General Pershing’s daughters in the film, “Pershing’s Crusaders.”

Dad’s dramatic coaching led only to such bit parts until one January afternoon when a crowd of us children were gathered on an icy Fort Lee hillside. We had been instructed to watch the child stars of the picture kiss each other before they tobogganed down the snowy slope. Wesley Barry, the freckle-faced male star, approached his leading lady to embrace her. But the scenarist hadn’t reckoned with feminine modesty. Wesley’s leading lady wouldn’t kiss him.

Instead, she dissolved in tears and refused to go on.

The director threw out his arms despairingly. “What do we do now?” he demanded.

“I’ll do it,” I piped up. I was astounded to hear myself say it. The idea of kissing a boy was shocking to me. I could feel the shame burning my face as everyone turned to look at me: if I could have sunk into a snowbank, I would have. But perhaps I was inspired by the disastrous memory of what had happened earlier when I wasn’t on my toes. In any case, Mother was beaming, and that was the important thing.

An onlooker called me over after the camera had taken its closeup. “What’s your name?” he asked.

“Lillian Roth,” I said.

He smiled. “My name’s Roth, too.” He turned to my mother. “I’m casting a show for the Shuberts and I’d like to see your child tomorrow. I think she’s just the type. We’re looking for a sad, pensive little girl.”

Next day I was in his office. “Honey, can you do a little acting for me?” Mr. Roth asked.

“Oh, yes,” I replied. “My daddy taught me ‘The Making of Friends,’ and I could do that for you.” I recited it, with expression. When Katie brought me home, I ran to my father and told him the good news. I had been cast for Wilton Lackaye’s little daughter in “The Inner Man,” a full-fledged Broadway production.

Daddy was jubilant. “See, Katie, what did I tell you!” He picked me up, threw me into the air, and kissed me. “She’s going to be a great dramatic actress. A tragedienne —that’s what. Why, she’ll be making $1,500 a week in no time!”

I had just turned six.

CHAPTER II

TRAGEDIENNE or not, I had to go to school, and during the run of “The Inner Man” Katie enrolled me in the Professional Children’s School. Classes were held only from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., but in the four hours you crammed a full day’s school work, including diction and French.

After classes Katie took me home, and when we were finished with dinner, made me up for my role as Mr. Lackaye’s daughter. I soon discovered there was a great difference between reciting Edgar Guest—even with expression—and performing on the stage. “The Inner Man” called for me to sit on the lap of Mr. Lackaye, who played a criminal finally redeemed by the faith of his little girl. One of my poignant lines was “Daddy, Daddy, won’t you PULLEASE come home with me?”

Mr. Lackaye gave me my first professional dramatic lesson.

“A play tells a story and you must pretend it’s really happening,” he explained. “You must pretend there’s nobody in the theatre—no audience, no one back stage-just you and me and the other actors. You must pretend I’m your real father. And remember—never, never look at the audience.”

He said this last so solemnly that my skin crawled. What awful terror lurked out in that vast unknown? After the second day I couldn’t hold my curiosity. For a breathless moment I lifted my eyes and looked directly into the forbidden darkness.

I almost screamed. Before me, as far as my eye could reach, was a weird ocean of pale, disembodied heads floating in a gray, ghostly dusk. I buried my face in my stage father’s shoulder, and tried to catch my breath. There was something about Mr. Lackaye that was strangely comforting. I snuggled closer: the odor of tweed, the fragrance of talcum, and through it all, the familiar, sweet scent of whiskey—why, I thought, it was just like being on my real daddy’s lap!

The Professional Children’s School was made to order for those of us already working. If you had rehearsals or matinees, your schedule was arranged accordingly, and there were even correspondence lessons if you went on tour.

As at other schools, the mothers waited outside for classes to let out, but since they were stage mothers, their conversation was studded with Broadway names and punctuated by the rustle of newspaper clippings passed from hand to hand. My classmates’ rollcall read like a theatrical Who’s Who of the future: Ruby Keeler, Patsy Kelly, Milton Berle, Ben Grauer, Helen Chandler, Gene Raymond, Penny Singleton, Helen Mack, Marguerite Churchill, Jerry Mann, and many others.

Sometimes I got out earlier than the other students and overheard the mothers on their favorite subject—the talent of their offspring. For example, Mrs. Grauer: “I really think my Bunny has one of the finest speaking voices I’ve ever heard.”

“Don’t I know?” This from Katie. “Didn’t I hear him recite ‘The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere? He was wonderful.”

Or Sarah Berle, with whom mother often played casino: “Katie, you should have heard Milton at the benefit last night! He tore the house down. When he did Cantor, you’d have sworn it was Cantor. And when he got down on one knee to do Jolson—”

Mother would interrupt: “Shubert came to him and said, ‘Get down on both knees, and Jolson goes!’”

They all laughed. They were proud of their children, and if Katie carried no clippings in her purse, it was because, as she once told me, “I didn’t have to carry proof, Lilly. Your name was up in lights.”

Milton Berle, who was several grades ahead of me but delighted in teasing me, did impressions, and even in those days he was accused of stealing someone else’s act Katie had taught Ann and me to save our acting for on stage: off stage we had to be perfect little ladies, like the little girls on Park Avenue. I couldn’t understand this, because Milton acted all over school. The moment the teacher left the room, he was running up and down the aisles, clapping his hands a la Eddie Cantor, and sending the rest of us into gales of laughter.

The prettiest of my schoolmates, I thought, was Ruby Keeler. I admired her slim, tapering hands. Mine were stubby, and looked even worse because I bit my nails. I was so self-conscious of my hands that I hid them when I talked; so nobody could see them, I snatched at pencils and books, succeeding only in dropping everything so often that I was nicknamed “Butterfingers.” Dr. Coué was the rage then, so I pulled hopefully at my fingers and recited, “Every day in every way the

y’re getting more tapering and more tapering, like Ruby’s.” Critics today, interestingly enough, speak of the way I use my hands to put over a song. I had to learn graceful gestures to draw attention away from my hands.

As I hid my hands, so for a long while I hid my voice. I knew Katie wanted me to be a singer, and I tried. Dad was always singing about the house. I followed suit. One afternoon, I was singing at the top of my voice, “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles,” the current hit, when Katie looked up from her copy of Variety. “Oh, Lilly,” she said, “that bubble really broke. That last note was way off key.” She shook her head. “Just like your father—you can’t even carry a tune.”

I never forgot her words.

After that I sang in secret, practicing in the bathroom where I turned the taps on full strength in the tub to drown out my voice. The rushing water became my orchestral accompaniment: it became drums, oboes, bass fiddles. I would be a singer when I grew up. I would make Katie proud of me.

Katie, to be sure, overlooked few chances for me. After “The Inner Man” closed, a stock company put out a call for a little boy, and I was turned down. Katie hurried me home, dressed me in a velvet Lord Fauntleroy suit borrowed from a neighbor, and rushed me back. “This is my son, Billy,” she said. I felt utterly disgraced, but I got the part.

Then Katie got word that Henry W. Savage was casting “Shavings,” and had interviewed scores of children for a 50 -page part. She had to be with Ann, who was playing in “The Magic Melody” that day, so she dropped me off at the producer’s office. She’d learned the play was about a toyshop, and she briefed me. “Now, do your best, baby,” she said. “And don’t be shy.”

Under orders, I approached the “Nothing doing” girl timidly, but with determination. “I would like to see Mr. Henry W. Savage,” I announced. She peeked over the desk to find me. “I’m sorry, little girl, but you can only see Mr. Savage by appointment.”

“Oh, well,” I said. “I have an appointment.”

She coughed to hide a smile, disappeared into the next room, and returned a moment later to say Mr. Savage would see me.

I walked into the adjoining room and stopped, transfixed. Behind a desk an enormous man was getting to his feet, rising taller and taller, until when he reached his full six feet four he seemed to tower over me like the giant in Jack and the Beanstalk. He was tremendous-massive, broad-shouldered, white-haired with a voice to match. It boomed out, rattling the ashtrays on his desk. “Good afternoon, young lady. I hear we have an appointment.”

I forgot all about my fib. “My mother told me you want a little girl to play a part in a toy shop,” I managed to stammer.

He looked down at me from his awful height. Suddenly he said, “How would you ask me, ‘Are you the windmill man?’”

All at once it came to me. That’s who he looks like— Thor, the God of Wind and Thunder. “Are you the windmill man?” I asked, in great awe. For all I knew, he was.

Mr. Savage said, “You have the part.”

“Shavings” put my name in lights for the first time. Just turned eight, I was billed as “Broadway’s Youngest Star.” Interviews with me were syndicated throughout the country. Wherever I turned, my face stared back at me, for photographs of Lillian and her one-eyed rag doll Petunia were placarded on subway pillars, telegraph poles and billboards.

Neither my photographs nor the growing scrapbook my parents kept meant much to me. What was exceptional about doing what you were told? Often I felt I’d have more fun with Ann playing Red Cross Nurse, helping the poor Belgian children orphaned by the Germans, a game all the other neighborhood children played. Now and then I stood in the wings and watched the rest of the show, but my eyelids would grow heavy, and Katie would take me into a dressing room, spread my coat over two chairs, and I would nap there until I was due onstage again.

Our home life, what we had of it, held little but indecision—and quarrels. My success, and Ann’s during our early years, only stressed our insecurity. We seemed either to be transients, away on tour, or, when we were at home, caught in endless bickering between our parents.

When Dad courted Katie, he was known as the handsomest boy on the block, she as the girl with the most personality. My mother was not beautiful, but she had an enchanting smile, and an immediate, warm sympathy that made her everyone’s confidant. Arthur’s charm was unmistakeable. Away from home he was merry and fun-loving, immensely popular. He began as a good-time drinker; then it developed into a problem, although liquor never took over his life as completely as it did mine.

Dad had big dreams. He tried his hand at everything, but never succeeded in becoming the man he wanted to be in the eyes of his wife and his children. He sold produce, then greeting cards, then men’s clothing; he was a stock and bond salesman; he even operated a waffle shop. One failure followed another. Each time he tried to pass it off lightly. “Well, Katie,” he would say, “that wasn’t for me, anyway.” And he would take a drink to forget it. I am sure, now, that ambitious as he was for us, his ego must have been hurt by the fact that Ann and I earned more than he, and that he was always going from job to job.

In time his drinking made him irritable and suspicious. Once, I remember, he accused Katie of poisoning our minds against him. She snapped, “If you ever saw yourself when you’re full of whiskey—how can they love you when you frighten them to death?” I watched, terrified of the blow that might come: once I had seen him strike her. I knew how explosive their tempers were.

As it worked out, however, we were separated from Dad for long stretches from my 9th to my 15th year. For after “Shavings” Ann and I became vaudeville headliners on the Keith Circuit, and Mother travelled with us. This meant three to four months on the road, then back to New York for a brief layoff, and back on the road again. Our act was “Lillian Roth & Co.” Ann was the “& Co.” until her great sense of comedy caused Katie to change the billing to “The Roth Kids.”

I did dramatic impersonations—impressions of Ruth Chatterton in “Daddy Long Legs,” and of “Pollyanna,” which I abhorred because she was “always glad all over.” My greatest thrill came in my impersonation of John and Lionel Barrymore in the duelling scene from “The Jest.” Here I could be the extrovert on stage that I could never be in real life. First I was John, taking my duelling stance, rapier in hand, my eyebrows cocked. “Methinks thou art a curl” Lunge, and back again. “Thou buzzard!” I roared. Jab, and dance away. Then, in an instant, I whirled about and became Lionel, transformed into the wily, cunning cackling-voiced swordsman who parried Johns violent thrusts with consummate disdain … The audience watched, silent and intent, and I was in raptures. I knew power, I glowed with the magic of the theatre, I felt the audience in the palm of my hand.

Then, bathed in perspiration and triumph, I bowed to thunderous applause and turned the stage over to Ann. My sister proceeded to throw herself into a brilliantly hilarious satire of my act. She burlesqued me down to the contemptuous curl of my imaginary mustache. The audience howled, and I suffered. The tragedienne in me was deeply hurt.

We played on bills with such headliners as Georgie Jessel, George Burns and Gracie Allen, Ben Bernie, and the Marx Brothers, and Katie taught us to curtsy to all of them, as was only proper with older persons. Rosie Green of Keno & Green, a comedy song and dance act, carried her baby, Mitzy, around in a little basket, and I often stopped to coo at her as she lay backstage laughing and gurgling.

“See my baby,” Rosie once said to me. “She’s going to grow up to be a great impersonator, too. Just like you, Lillian.”

“Like me? Gosh,” I said, flattered. I was all of 10 years old.

Once, in Washington, D. C., Ann and I were told that the President of the United States was in his box that afternoon. After the show the stage manager hurriedly knocked at our dressing room door. “The President wants to see you, kids!” he exclaimed.

Still in our costumes, we rushed out the stage entrance into the back alley, and there they were, President Wilson

and the first lady, sitting in a huge open touring car. The President asked us to get in. Ann sat on his lap. I sat shyly between him and Mrs. Wilson.

“What a serious little girl you are, both on and off the stage,” the President said to me. “You know, I am going to make a prediction, young lady. Some day you will be a great actress.” Then he turned to Ann. “And you, my dear, you were utterly delightful. Mrs. Wilson and I haven’t laughed so much in a long time”

I found my voice and thanked him. Ann, busy examining and fingering the interior of the luxurious car, piped up, to my mortification, “Ooh, what a big auto! My daddy has a tin lizzie.” The President smiled and turned to Mrs. Wilson. “Shall we take our little guests for a ride around the block?” Away we drove. When we emerged into the street outside, it was jammed with people held back by police on both sides. They waved and applauded as we passed by, and then we were brought back to the stage entrance again.

“Goodbye, little girls, and stay sweet,” Mrs. Wilson called back to us as their chauffeur drove them away. I thought, as we went to our dressing room to put on our street clothes, it was just like a beautiful fairy tale—like Cinderella’s ride in the pumpkin coach.

Mostly, however, vaudeville on the road was a hard life, made up of lonely train rides (even now a train whistle fills me with haunting sadness), lonely nights in strange hotels, and lonely cities in which we knew no one. “The Roth Kids” in lights in town after town meant little to us. Wistfully Ann and I looked out the train windows, watching the endless procession of backyard gardens flow by, catching a glimpse of little family groups, of children playing with their pets, of mother and father contentedly together on a back porch. We yearned for a home, a garden, a hammock, a sense of belonging.

Like prisoners Mother, Ann and I counted off the days until we got back to New York. “Where do we go next, Mommy?” I would ask. Katie would produce a long slip of green paper. “Hattfield, for three days.” “Then where, Mommy?” “Pittsfield, for a split week.” And so it was— four days, three days, and week stands, month after month.

I'll Cry Tomorrrow

I'll Cry Tomorrrow