- Home

- Roth, Lillian;

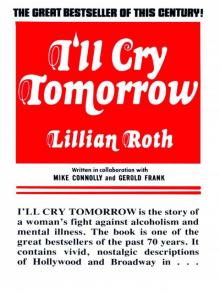

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Page 17

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Read online

Page 17

The bottle was on the table next to my bed. From it came delirium, but from it, too, sometimes came oblivion.

Minna said, later: “You suffered hallucinations. You thought you were battling tigers and lions. ‘They’re trying to destroy me and I won’t let them,’ you moaned.

“Once you imagined I was a mummy. ‘Minna!’ you shouted, ‘You’re frightening me. You’ve turned into a mummy in front of my eyes! I see you as you were 10,000 years ago! How can that be? Why do I see you that way?’

“I tried to comfort you by saying it was your overworked imagination stimulated by alcohol, but I was frightened myself.

“Then you said, ‘I’ve got to finish the bottle. I don’t care what happens. I’ve got to finish the bottle. I want death.’”

I was in agony. The blinds had to remain drawn in the room; daylight seared my eyes. My sinuses were inflamed, my nose congested. I found it hard to breathe. My arms and legs ached with neuritis.

Mother and Edna called Judge Shalleck. Shocked at my condition, he sent me to his doctor. The verdict was impending blindness, the onset of cirrhosis of the liver, advanced colitis, and a form of alcoholic insanity. The reports from a nose-and-throat specialist, an Ophthalmologist and an internist confirmed these. I had drunk myself into gibbering helplessness. Death was not far away.

Edna pleaded with me. “I know,” I said dully. “I’m trying to stop. I’ve cut to a pint a day but it isn’t enough. I have to have more to stop the pain and what I’m hearing and seeing. I’ll never pull out of this.” I became maudlin, gay and maniacal in turn.

A neighbor, alarmed, took Katie aside. “Mrs. Roth, you can’t live with your daughter, as much as you love her. She might murder you in your sleep in one of those drunken rages,”

I could not keep food down. I vomited all morning. At night my colitis was so agonizing I could not remain in bed. “I don’t even know how to kill myself,” I wept to Edna. “I’m not even good enough for that.”

Each day I begged for more liquor. “What can I do?” I cried. “I’ve got to have more” I could not bear the pity in her eyes as she gave me a couple of dollars.

The moment I crossed the threshold of a liquor store, I began to shake uncontrollably. The thought of the drink I would soon have completely unnerved me. With two dollars I could buy only a pint, but I was ashamed, for it was a dead give-away: only drunks bought so small a quantity. I improvised. “I just want enough gin to make a couple of martinis—do you think a pint is enough?” I asked the clerk, who had only to look at me to know the truth. Or I said, “I’ll take a fifth of gin,” opened my purse and exclaimed, chagrined, “Oh, dear, you’ll have to make it only a pint. I didn’t take enough money.”

Finally Edna sat down with me. Was there no one, no one in the world, who could help me? No one I trusted to help me? And suddenly, out of the limbo of sixteen years, there flashed into my distraught mind the name of Dr. A. A. Brill, the psychiatrist to whom I had gone so long ago.

Edna took me to see him the following day.

Dr. Brill had my medical history before him when I entered. His eyes were kind and his smile understanding as he rose to greet me. “You are a little late for our appointment, aren’t you, Lillian?”

The flood gates opened. “Oh, Doctor!” I cried. I paced wildly back and forth, trying to find the words to tell him in a few minutes all I had suffered during those sixteen incredible years. “I’m in such pain; I’m so sick! The things I see and know I see! The things I hear and know I hear! The people coming at me who think I know something about saving the world, and I can’t think what it is. When I walk I think I’m falling in space, that buildings are crashing down on me, that bridges collapse when I cross them. I can’t eat, I can’t breathe, I can’t see, I suffocate, I vomit, my hands are stiff, I can’t told anything, I’m so ashamed of myself, I’ve sunk so low … I’m hopeless! I’m hopeless! Nobody can help mel” I fell into a chair, sobbing.

Dr. Brill talked to me, quietly, and examined me. He sent me into an anteroom and spoke to Edna.

“She is at a breaking point physically and mentally. I don’t give her three months to live unless she’s hospitalized immediately.”

Would that help? Edna asked. Would it stop the drinking?

He shook his head. “I can promise nothing. I can only tell you, if you want to prevent her death, she must be taken to a hospital at once.”

“Will you tell that to her?” Edna asked. Dr. Brill smiled sadly, as if to say, what difference could that make? “Very well,” he said. “Bring her in.” Edna led me back to his office.

“Lillian, I have just told Miss Berger what I am going to tell you. You haven’t more than three months to live.”

I stiffened, but remained silent. The blood slowly drained from my face.

“There is a chance to save your life. You must be put in a hospital at once.”

I broke down. “I’ll do anything,” I wept, “anything. I don’t want to be a burden. I want to be a human being again. I’ll do anything you say.”

Dr. Brill told Edna he would arrange for my admittance into the Westchester Division of New York Hospital—a mental institution.

Later he telephoned her to say they would accept me in ten days. I must commit myself and remain six months to a year. I waited.

One night Ann, who had no idea how ill I was, took me to see “The Lost Weekend,” a film about an alcoholic. She hoped it might shock me into sobriety. Instead, when Ray Milland, the star of the film, watching a drinking scene on the screen, yearned for the bottle he had left in his coat in the checkroom, the effect upon me was startling. I wanted a drink so desperately I had to restrain myself from rushing out of the theatre to a bar. I suffered like a person on the rack until the picture ended: then, at the first chance, I drank myself into insensibility.

The morning came when I was to enter the hospital.

“I’m worried,” I said nervously to Minna. “I think it’s really Bloomingdale’s I’m going to, and that’s for insane people.”

Minna denied it. So did Edna.

Whatever place it was, I made sure I would not go unprepared. I bought six two-ounce medicine bottles filled them with gin, and put them in my bag. The usual fifth might be too conspicuous.

Edna and Minna drove me to the hospital: Mother remained behind. Dr. Brill had warned that if she came along, at the last moment I might change my mind and refuse to commit myself. I sat quietly in back with Minna, drinking to keep up my courage.

We stopped once, when Edna asked a gas station attendant:

“Which way to the Westchester Division of New York Hospital?”

“Straight ahead, ma’am,” he said briskly. “You can’t miss it—Bloomingdale’s.”

I began to babble. “Listen, I heard about a woman who went to Bloomingdale’s. They gave her needle baths and put her in straitjackets and beat her with rubber hoses. Please, I beg of you, don’t take me there!”

They soothed me. “Oh, no, dear, it used to be Bloomingdale’s. Now it’s only for people who are a little upset.”

There was nothing I could do. When finally we drove through the huge iron gates and along a winding driveway and came to the great formidable red brick building, I said to myself: “When I was a little girl, I thought someday I might want to be a mm. Maybe this is my way of being a mm. This is my convent. Maybe God has sent me to this place. I’ll just go in and give myself up. I have no other place to go.”

Estelle Demarest had given me a small pocket Bible. I clutched it tightly in my hand as we walked into the building.

The receiving doctor wrote down my name.

I made a last attempt to remain in the world. “I wonder, Doctor, whether I’m not making a mistake coming to a place like this. I have extra-sensory perception. In Niagara Falls I felt things other people didn’t. Just last night I told Edna that we’d contact the moon and this morning’s newspaper says we had contacted the moon by radar. Doesn’t that prove I don’t belong he

re?”

“Now isn’t that interesting?” the doctor said. “You just sign right here, please.”

Then I knew it was no use. What good was my intuition, if people refused to believe. Perhaps if I had gone to college I might have been able to explain what I meant All right, I’ll sign and go in. But I forgot my pocketbook. Might I return to the car and get it?

The physician nodded. “Of course. But come right back, please.”

My bag was in the car, but the bottles were gone. “Edna!” I cried, “you took the bottles!” She shook her head. “Minna! Then you’ve taken them!” She swore she hadn’t.

I was crushed. How could they do this to me, refuse me one last drink? I returned to the reception desk and stood there, shaking uncontrollably. If only I could have had that last drink and gone in like a lady!

CHAPTER XX

FOR THE FIRST TIME in my life I fell on my knees and prayed. “Dear God, I thank You for giving me sanctuary and keeping me from destroying myself.”

I rose trembling and sat on my bed. I was in a small room, with a bureau, a gray metal clotheslocker, a straight-backed chair, and a single window covered with vertical iron bars. There was no door.

A few minutes before a nurse had led me down a long red carpeted corridor to this room. I had a bobby pin in my hair; deftly she detached it and put it in the pocket of her uniform. She took away my necklace; my wrist watch; my garters. She searched me for other objects with which I might harm myself. She placed my clothes in the locker, and used one of the many keys on her belt to lock it. Then she helped me into a nightgown buttoned up the back, and left me a long beltless robe and slippers.

I had just begun to absorb my surroundings when three men entered. It developed that since I had committed myself, I was a ward of the State, and these were physicians to interview me. This will be a breeze, I thought: I’ve been interviewed before. I realized how I must have appeared, in my shapeless hospital nightgown, my hair in strings, my robe flapping about my ankles, but I bowed graciously. “Come in, gentlemen, please.” I sat on the bed and they took chairs. One rose courteously: “Wouldn’t you like to sit here? It’s more comfortable.”

“Oh, no,” I said, sitting up stiffly. “I prefer to sit in straight-backed chairs.” They exchanged glances. There, I’ve done it, I thought. Of course I know I’m sitting on a bed. What I meant is that I like to sit up straight. But let it go.

One physician took up the interview.

“You signed several statements when you entered, Miss Roth. We want to see if they are correct, because we must take care of you. We represent the State of New York.”

“But I’m not a State case,” I said. “I’ve come to a private hospital.”

“Yes, my dear, but you’re under our jurisdiction and we must protect your interests. Now, is it true that you feel you’re going blind?”

That was right. I had signed that. “Yes,” I said, “your faces aren’t very clear to me. Sometimes everything floats in a gray mist before my eyes and I can barely make out vague figures moving about.”

“Do you have dryness of the throat, pain and inflammation of the sinus?”

Yes. Yes again, yes. Item by item they proceeded through the long catalogue of my suffering.

“And you have had various thoughts of suicide?”

I had to tell the truth. I had signed that statement. “Yes.”

“Do you hear voices?”

“Yes. Sometimes I think the radio is on when it isn’t.” I paused. “But I do feel psychic—as though people are trying to get messages to me.”

“What kind of messages?”

“Telepathic messages.”

One doctor asked:

“Why do you think you have such a strange power?”

“There’s nothing strange about it,” I retorted. “Don’t they do things like that at Duke University? I’ve read that university professors in London have communicated telepathically, too.”

“Yes,” said the first doctor. He looked at his notebook.

I wouldn’t tell the truth. “When I’m upset, I see spots before my eyes, but don’t you see spots when you overeat?” I thought, I must show them I’m not as insane as they probably think I am. “Right now I can see the tie you’re wearing, and it’s a very nice one.”

“Do you like the pattern?” he asked, politely.

“Yes, and the color, too. I always chose the judge’s ties for him, and I can tell a good Sulka tie when I see it.”

There was a moment’s silence.

“Did you make a statement that you would write a book here?”

“That’s right.”

“What about?”

“I was going to clear a man named Jimmy Hines.”

The notebook closed. “Thank you, Miss Roth. That’s all. Thank you very much.” They left.

I was alone. A few minutes passed. While I had been questioned, I had heard sounds of people moving in the corridor, the jingle of keys on the belts of the nurses. Now everything was silent. Some of my confidence began to melt.

I ventured out of my room. The corridor was empty, and I strolled down it. Small rooms like mine lined it on either side. I peered into them. Each was empty. Where was everyone?

I turned at the end of the corridor and found myself in a large, library-like room. It, too, was deserted. I wandered over and tried to pick up a book, but my fingers were too stiff.

Suddenly there were butterflies in my stomach: my hands shook, I was all alone. “Oh, Mom,” I cried soundlessly, “Where are you!”

Then, a slight stir. I turned. A handsome, black-haired, ruddy-faced young man was at my side. “How do you do, Miss Roth,” he said cheerfully. “I am Dr. Head, your psychiatrist How do you feel? Are you nervous?”

“Do you see things?”

“Oh, no,” I said hurriedly. “I’m a little worried about what will happen to me. I really don’t know why I signed in here, Doctor.” I thought, he’s cute. I wish the nurse had left me a comb or lipstick.

“We want to take a few simple tests,” he said. He looked at me. “Don’t you think you’d like a pill first to quiet your nerves?”

“No, thank you.” I was firm. I was not asking them for anything. “I’m just fine, Doctor, just fine.”

He told me to sit down, and gave me a complete physical examination. He had me walk forward; then backward; then sideways; then on my haunches. “My goodness, Doctor,” I protested. “I’m a singer, not a contortionist. Please!”

He laughed. “Miss Roth, I’m just trying to judge your sense of balance. Now, will you please get on your knees and walk across the room that way?”

I gave him an arch glance. “Shall I sing a chorus of ‘Mammy’ enroute?” Katie would have liked that.

Dr. Head laughed again. “We’re going to get along fine, Lillian,” he said. “We’re finished for a while now.” A nurse silently appeared, and led me down the corridor to a huge living room in which about fifty women sat at their ease in lounging chairs and sofas. They were all well dressed: they might have been guests at one of my charity affairs.

For a moment I was the judge’s wife again. “Hello, everybody,” I said gaily. They all stared straight ahead. Each remained lost in her own private world. I sank into an empty chair, to find myself next to a pretty girl, about 23, who was in an animated conversation with someone who wasn’t there. She talked so swiftly as to be almost unintelligible: her lips moved, she nodded, simpered, raised her eyebrows in astonishment, then listened intently.

As I watched her, the enormity of it struck home. These were mad women! What was I doing among them? I could not catch my breath: I felt my heart leap in my throat: I began to shake. Oh, God, I’m getting the horrors. Don’t let them get too bad or they’ll put me in a straightjacket.

A bell rang. The women rose like automatons, formed a line, and began to file out. “You go with them, Miss Roth,” a nurse called. “It’s lunch time.”

“But I’m not hungry,” I prot

ested.

Her voice took on the tone of authority. “You go ahead. You’ll eat.” I followed the others into a large dining room and sat down. I fumbled for a knife and fork: they fell out of my hands onto my plate with a loud clatter. An attendant tried to feed me with a spoon, but I gagged: my throat was too constricted. The shakes came on me with renewed fury. Sweat poured from me. The room began to spin, and slowly I started to slide off the chair.

Strong arms half carried, half helped me to my bed. I lay shaking so violently the springs creaked. I thought in panic, now I’m getting it. I’ve got to control this, or they’ll lock me up and I’ll go mad. I can’t let them know. Screaming inwardly, I struggled out of bed and asked the nurse on duty in the corridor: “Isn’t the doctor coming?”

“Yes, there’ll be a doctor here soon.”

I tried to wait in my room, but the nurse sent me back to the living room. I paced back and forth; my legs were getting stiff, I could scarcely bend my knees. My jaw began to tighten, my teeth seemed to loosen in my gums. A strangling sensation crept over me. I’m going stark, raving mad. A knife, a knife to plunge into my stomach and twist up to my heart, like the Japanese, tear myself wide open to end the agony…

I had never known such torture. In the world outside I was always confident that I could find a drink to ease the pain. Here I was utterly helpless, and if I betrayed any sign of the hell I was going through, they would put me in the mad ward…

I walked the infinite distance to my room, step by step. When, ten minutes later, a doctor entered, I was sitting on the bed, soundlessly pounding the mattress with my fist. I looked at him, unable to speak.

“Give her an ounce of paraldehyde,” he told the nurse.

I'll Cry Tomorrrow

I'll Cry Tomorrrow