- Home

- Roth, Lillian;

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Page 16

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Read online

Page 16

That the enemy could draw my knowledge away telepathically weighed heavily on me. Perhaps drinking would be considered patriotic under such special circumstances, I reasoned. If I became muddled with liquor, I’d confuse enemy agents: they’d tap my brain and get nothing but mental static. I liked the idea.

Fortunately, it seemed that I was vulnerable to the enemy only on cloudy days, for everyone knows the sun weakens radio waves. On cloudy days I hid in my darkened room, drinking patriotically and avoiding the mirror. On sunny days, I ventured out.

One afternoon, strolling serenely with my dog, I passed a church. Near the door a neat printed sign read: YOU ARE WELCOME. ENTER AND REST. On impulse I walked into the dark, cool interior and slipped softly into a pew near the altar. Oh God, I thought fleetingly, if You are in this church, help me: I cannot understand what is happening to me. I looked to one side. There was a large, life-size statue of Christ on the cross, the face marked with pain. I felt very humble. It occurred to me, with surprise, that I was sitting in a chinch with a dog. But wasn’t a dog God’s creature, too?

A bell tinkled. A priest, genuflecting as he passed in front of the altar, glanced at me. For a moment our eyes met, and held. Then he disappeared through a door at the side of the altar.

I walked dreamily out of the church, into the warm, terribly bright sunshine. Was not the meaning of the glance between the priest and myself clear: Do not hide any more. You are in God’s world and you are welcome. You do not have to hide any more.

“Vic,” I said that night. “Let’s leave this town. I’m sure my nerves will straighten out if we go back to California. And I might get a few bookings there.” Victor, who was bored with the Falls, thought that a good idea. We could live with his married sister in Los Angeles—she had an eight-room house—until I earned enough money to rent an apartment for us. But where would we get money for fare to the coast? What with our hotel bills, and my two quarts of liquor a day, we hadn’t been able to save anything from Victor’s salary.

I phoned Katie collect and she sent me a money order for $600, every cent she could scrape together. She had obtained it by pawning what she had left of the jewelry Ann and I had given her through the years.

Once in Los Angeles, Victor got more money by selling my silver fox cape for $50—the last fur I had, which Mark had overlooked.

At his sister’s house I tried to taper off on a quart of wine a day, the cheapest drink I could buy. Victor obtained a job in a credit jewelry store. I had little to do with his sister, her husband, or their three children, aged twelve to seventeen. Instead, I spent my time in our second-floor guest room, sipping wine and poring over the Bible.

If God wanted me to hide no longer, I must read His book. Marie Stoddard wasn’t here to help explain the difficult passages, but certainly the Bible should partially insulate me from the vibrations, the radio waves, the spectral faces, the enemy agents trying to siphon away my secrets.

Victor and his sister had words about me. Her voice was shrill and carried to our room. “I’ve got children in this house! I won’t have her here. Not another day.”

I opened the door and came to the head of the stairs. “You needn’t shout,” I said clearly. “I understand.” I heard her voice again. “I’m going out to shop. All I say to you is, be sure she’s out of here by the time I get back.”

I approached her later. I asked carefully, “Does Vic want to get rid of me, too?”

She said, “Yes. You’ll have to leave today.”

I packed a bag and left. I ventured to ask some friends if they would put me up overnight until I decided what to do. They politely declined. I stood on a street corner, bag in hand, bewildered. I could not wire Katie that Victor had put me out. I walked aimlessly. How would I get into a hotel? They were crowded because of the war. From some dim recess of my memory, Christian Science came into my mind. A few minutes later I was in a Christian Science reading room. The words trembled before my eyes: “In my Father’s house are many mansions.” I walked out of the reading room into a drug store and fumbled through a telephone directory.

Hotels…hotels…My fingers stopped shakily at Hotel Christo. That was enough. The name was a sign. I telephoned the clerk: a man had checked out a few minutes earlier—a room was available if I came over at once.

It was among the cheapest one-night hotels. “I must be humble,” I said to myself. “Didn’t Mary Baker Eddy say that Jesus Christ was humble?” The curtains in my room were filthy, the furniture ancient. A Gideon Bible lay on the table which was pockmarked with the butts of a thousand cigarettes held in the vanished hands of a thousand lonely souls….

I undressed, got into bed, and fell asleep with the Bible under my pillow.

I awoke suddenly, light-headed. I was alone, the first time in my life I was absolutely alone. God, I thought, will take care of me. He will provide. The morning sun streamed in, a bright pathway of dancing dust motes in the murky gloom of my room. I tinned my eyes away: the bright light burned….

I was lying in bed, looking up. The curtains fluttered, as if teased by a gentle wind. They parted slowly, and a white figure appeared with two men on either side. The figure was Christ, dressed in white, a gold band about His forehead. I could not recognize the others. They wore dark skull caps and dark clothes. The Figure approached me. His hand seemed to float forth and with infinite tenderness passed over my hair. My eyes closed, and I slept.

The shrilling of the telephone awakened me. “I’ve been looking everywhere for you.” It was Victor. “Lil, I did the wrong thing. We’d better get together. Well work something out.”

He took me to an apartment, but he was away most of the day and night, returning only to supply me with yellow pills. I took the pills to sleep, and the liquor to bring me out of the lethargy of dope. The combination tore at my nerves. When I tried to walk, or do anything at all, I went into raging tantrums at my inability to function.

Then Victor left me. He never said a word. He had had enough.

Everything became confused. An elderly man from the film colony who had known me since “The Roth Kids,” unaccountably appeared in the room and tried to make violent love to me. Now I was in the street, clutching the arm of a soldier, begging him to come to my room and “get that ugly old man out of there.” Now I awakened from a heavy sleep. It was daylight The old man and my landlady were chatting at my door. “I knew her mother and father,” the old man said. “I’m a good friend of the family.” “Well, I’m glad, poor thing,” said my landlady as she left. “Do take good care of her.” The door shut behind her, and the old man turned toward me with an odd smile on his lips. I tried to cry out, and then I was asleep again.

Was it an hour later, or twelve hours later? I opened my eyes. A thin, effeminate young man was in my room, drunkenly trying on my dresses. It was unreal as a dream. Was I back in Chicago, at “Artists and Models?” Were we preparing for the party in the barn….

“Get out of here!” I moaned.

“Hi, Lillian,” be said. “My name’s Lionel. Vic sent me to watch over you. I won’t bother you.” He giggled.

I began to wail.

“All right, all right,” he said. “I’ll go.”

Then it was night again, and I lay half conscious on the sofa. I heard a whisper, as from far off: “Lillian, Lillian, Lillian.” It came from the ventilator. There was no one in the room. Am I going mad? I looked at the clock: it showed three o’clock, and it was dark outside. “Lillian!” the voice whispered urgently, and the ventilator rattled. I stumbled out of bed and found the landlady. “My God, see if I’m going crazy. Is there somebody in that ventilator?”

In her bedclothes she rushed to my room. She opened the grate and looked down. Lionel was there, in the basement, drunk. He had been watching to see if any men visited me. Later I realized Victor had brought me to the room in hope men would call on me so that he would have grounds for divorce.

I slept, and woke again. Now everything was gone. My radio, m

y records, my clothes.

In one awful, lucid moment, I paced back and forth in front of the jewelry store where Victor worked. I grabbed his arm when he emerged for lunch. “Vic, I need money. You’ve taken everything. I got to have a little money—enough to get by. I have to pay the rent I have to eat.”

He pushed me away, and walked on. I struggled after him, clutching at his clothes. “Get away from me,” he said hoarsely, under his breath. “You’re just a drunken bum. Get away from me!”

“I’m not drinking, Vic,” I gasped, laboring after him. “I promise you. For God’s sake, let me have a few dollars.”

He turned on me, his face white. “Get away from me, you—”. Words failed him. “Get—or I’ll call a cop, you miserable, no-good bum!”

Days later I sat dully in a lawyer’s office. Victor had sued me, and on his terms. “Let him get the divorce,” the attorney advised me. “Or he’ll drag you through the courts with your drinking, and that old man, and all the rest.”

“I tried to keep the old man out,” I faltered. “He had a key and the landlady let him in. Half the time I didn’t know he was there.”

The attorney sighed. “And throw away those pills your husband left you. They keep you all doped up. You’re passed out most of the time.”

I sat numbly. The door opened and the lawyer’s secretary came in. She had a stunned look on her face. “President Roosevelt is dead,” she said in a hushed voice.

Why annoy the lawyer further? The entire country had suffered a great loss. “Do what you think best,” I told him. On the way to the elevator I stopped in the ladies’ room and took a long, comforting drink from the bottle in my bag.

No one offered to help me in the days that followed, save a poor woman who lived in two rooms above a Chinese laundry. I do not remember how I met her. I remember visiting her, laboriously toiling up the steps to the hovel in which she lived, playing with her children, trying to ignore the roaches scurrying across the floor. She alone offered me food, which I could not eat.

And then—a long, blank period.

I did not know it, but I was not altogether forgotten. There was still my mother, in New York.

Katie, with hardly a penny to her name, was living with Ann’s motherin-law, for Ann’s baby had arrived, and there was no room for Katie there.

Among the few people my mother saw were two friends, Estelle and Phyllis Demarest. At their apartment she met Edna Berger, who lived next door. Edna, a warm, outgoing and extremely resourceful girl, was international representative of the American Newspaper Guild, a job which took her out of town much of the time. She liked Katie, and often talked to her about me.

One evening my mother visited the Demarests, and Edna dropped in. Katie was obviously under great tension. Finally she brought out a letter she had received that day. It was from the lawyer I had seen about Victor’s suit for divorce. He had written that I was practically on the streets. Victor had left me. “She’s without funds, Mrs. Roth,” he wrote, “and seems to be a chronic alcoholic. She seems to be taking drugs of some kind. She’s not rational. I advise you to come out and get her.”

There was an embarrassed silence. Katie began to cry. “She’s my child,” she wept, “and drunk or sober, she’s been a good daughter. I must help her.”

“Katie, how much money will it take to bring Lillian here?” Edna asked.

“If I could send her $150 for fare—”

“All right,” said Edna. “You have it. We can’t let that girl die. We’ll send her the money to come here so you can take care of her”

Katie sent me a money order for $150.

Ten days passed without word from me. Edna called the West Coast, checking with everyone who might know my whereabouts. They found me living in a small hotel. I had spent the money for liquor, pills and toys for the children of the woman who lived over the Chinese laundry.

“Since we’ve gone this far,” Edna said to Katie, “let’s go through with it. Here’s money to buy a ticket. Go out there and bring her back yourself.”

With great effort I managed to be at the station. My mother, her face pale and strained, came off the train and walked by me. She had not recognized her own daughter! When she did, she wept like a child. “What’s happened to my baby?” she cried. “What have you done to yourself!”

In the cab I lay against her shoulder. “I can’t help it, Mom,” I wept. “I can’t live without liquor. And I just couldn’t make the trip back home alone.”

“What will we do, Lilly?” my mother asked in despair. “Oh, my God, what will we do!”

She rented an inexpensive room for us and obtained a job for $20 a week in a five-and-tencent store so that she could care for me until the divorce came through, and provide me—even though she loathed it—with at least a pint of liquor daily so that I would not go completely out of my mind.

This I thought—my mother working in a five-and-ten—was bottom. My pride, my dignity—both were gone. This was the state to which I had brought the mother of Lillian Roth, whose name had been in lights from Hollywood to New York, who had ridden in gold-plated Hudsons and had earned over a million dollars before she was thirty! My mother, whom I wanted to give everything in the world.

On the lowest morning of all, I went to the California State Employment Office and filled out the necessary blanks. What kind of job, they asked? I could think of nothing I was fitted to do. Finally I wrote, “receptionist.” My tears blotted out the word.

BOOK TWO

CHAPTER XIX

ALL RIGHTS, Lillian, let’s have a little heart-to-heart talk with yourself. Let’s admit it: you’re a hopeless drunk. It’s not easy to become a hopeless drunk. You must work at it—and you certainly did. You thought a drunk was someone who falls in love with liquor at first sight, and drowns himself in it. You know better now. You know that alcohol creeps insidiously into your life, so insidiously you aren’t aware of it until it’s too late. Now and then someone will say, “Aren’t you drinking too much, Lillian?” You smile at that. You think, “Well, maybe I have been taking a little bit too much to drink, but heavens—I never feel anything the next day. I have wonderful recuperative powers. I still do my shows, and I manage all right. Good Lord, I would never be like that person, I mean, that famous singer who died of liquor— I mean, that’s so silly, well, I just couldn’t be that way….”

Well, you could, Lillian. Trace it back yourself. In the Vanities, after that European trip, remember? It was four or five whiskey sours a night. Hangover the next day, but you managed until the next night. Soon the four or five became a pint, and then a fifth. And you couldn’t start the morning without a drink. First it was beer; then bourbon in orange juice. (What had that Hollywood star suggested: half gin, half lemon juice?) Then, the two-ounce bottles in your bag grew to six ounces, and finally fifths…. Odd, no one ever commented (except Mark) that you were rarely seen without those big handbags. Well, good reason, reason enough.

Soon you were on a fifth a day, taking the stuff slowly, a drink or two every four or five hours. Then, every three hours. Then two hours. Finally, every hour. Then a quart through the day, and a quart through the night; and if you weren’t drinking too swiftly you reached a kind of sober-drunk, where you weren’t hung over.

“Well,” you thought, “at last! I can finally hold my liquor.” What a laugh! You didn’t realize you were pouring it into yourself so steadily that you couldn’t have a hangover because you were always drunk.

As the years went on, something terrifying happened. You couldn’t hold as much. You began to throw it up. One part of you cried, “I want it!” The other part cried, “I can’t take it!” Your body reached a point of revolt: you simply could not hold it. You drank, and you threw up. You were sick all the time. Sometimes you vomited all morning before your stomach retained an ounce of it —the drink your body needed so desperately.

The next stage was worse. You lay in bed and drank around the clock: drank, passed out, waked, drank

, vomited, drank, vomited, drank, passed out….

Then, still worse, the shakes. Your system demanded more liquor but your system refused to accept it. The punishment was the shakes; and with the shakes, agony. Eyes, nose, sinuses, head, throat, chest, stomach, legs…. Only liquor could relieve it, but your body rejected liquor. And after the shakes, the horrors, the delirium tremens, when you heard sounds that were not there and saw things that did not exist, your being was one gigantic, inflamed, tortured mass of mental and physical anguish…. Then the hours of pacing your room, and tearing your hair, and you have reached the worst stage of all: your medicine is your poison is your medicine is your poison and there is no end but madness.

Edna told me later:

“Katie brought you back with her from the coast in December, 1945. I was about to go off on a Guild assignment. Now, you must remember [said Edna] I had never met you. I remembered you as a child star, and I had always admired you tremendously. We were the same age, but when I was a 20-year-old college student, you were already a Hollywood star.

“Katie walked in with you. I was horrified. I had never seen a human being in such a state of helpless drunkenness. You seemed less than human, like a whipped animal, completely submissive, scared to death. And your appearance! Your hair was wispy and straggly: your face and body were bloated, but your arms and legs were thin as pipe-stems. I cried when I saw you.

“‘What will I do?’ Katie said. Where will I take her? I said, ‘You’ll stay here and take care of her. You might as well use my apartment while I’m away.’”

Edna went on her assignment. Minna came in from her home in the Bronx to stay with Katie and me. I drank. I had to drink. Sometimes, when Katie, completely exhausted, went to bed, Minna sat up until dawn with me. She went through the DT’s with me. I clung to her: deep in my alcohol-soaked brain, she represented a subtle kind of comfort. She was one person (not from the confused, nebulous world in which I had lived, but from the solid world of everyday people), who remained my lifelong friend. I clung to her and to this one tie with normalcy which I had been able to maintain despite everything, this one sound, healthy relationship I had built through the years which alone had not crashed.

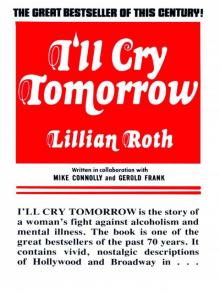

I'll Cry Tomorrrow

I'll Cry Tomorrrow