- Home

- Roth, Lillian;

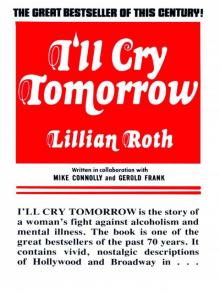

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Page 5

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Read online

Page 5

One of my worst nights was when Ziegfeld let Rinker, Barris and Crosby go. I had a quiet crush on Bing. I loved his casual singing style, the way he clashed a cymbal as though clashing one was the last thing he wanted to do. Ziegfeld, just back from a European tour, apparently decided the cymbal didn’t fit in with the lofty tone of his show. The Rhythm Boys had to go.

Offstage, Bing was mild-mannered and quiet, a rather lonely person who seemed to need mothering. When he crooned in the style that later made him famous, shivers ran up and down my spine.

Often, after the show, knowing Katie’s fear of the night, Bing walked us through the lonely streets to a well-lighted section near where we lived, bade us a gallant goodnight, and sauntered off. Katie had a way with lonely people; they liked her, and she was comforting to them. After the trio was let out, I asked Bing what he thought he might do next.

“I don’t know, honey,” he said. Then, thoughtfully, “We might go out and take a look around Hollywood.”

CHAPTER VI

WHEN my big break came, it came suddenly. Al Jolson’s “The Jazz Singer” burst upon the world and launched the “Talkies.” It sounded the doom of vaudeville; and it also posed the question: how many ways could the human voice be used on the screen?

Shortly after I opened in the Frolics, Jesse Lasky of Paramount tested me for something new in films—one and two reel singing shorts. I went before the camera and sang some of my popular songs directly to the audience, trying to achieve a rapport with them until they actually sang in their seats.

The test was successful. “Why these short subjects then?” I asked Mr. Lasky. “Why can’t I get into a big picture?”

“It doesn’t work that way, my dear,” he explained. “A director must see you and send for you. They must want you for a part out there.” He added kindly, “But I’ll keep an eye open and if anything happens, I’ll let you know.”

A few weeks later I hurried down to the Criterion Theatre to see the premiere of my first short, in which I sang, “Ain’t She Sweet!” On the same bill was Maurice Chevalier’s first American picture, “Innocents of Paris,” and I was eager to see that, especially since Mr. Chevalier himself was a guest celebrity at the Frolics that week.

My hopes were dashed a moment after my short flashed on. Was this how I appeared on the screen? How could I ever dream of being another Garbo or Barrymore? I wrinkled my nose, I screwed up my face, I blinked, my smile was definitely crooked …

Then Chevalier’s picture. I was entranced. His charm and gaiety filled the theatre. That night I stood in the wings at the Frolics and saw the great French star sing “Valentina,” wearing his famous straw hat, grinning his captivating and oh-so-crooked smile, letting the magic of his warm personality work its wonder on us. The audience cheered itself hoarse.

Yes, I thought, as I returned to my dressing room, you always know when you’re in the presence of a great Either you had it, or you didn’t—

“Miss Roth—”

It was a stagehand. Mr. Jesse Lasky and Mr. Ernest Lubitsch were in the house and would like the pleasure of my company at intermission.

Mr. Lasky introduced me to a little man with a big cigar, who seemed to whistle under his breath as he rose. “Mr. Lubitsch,” said Mr. Lasky with a twinkle in his eye, “is interested in you, Lillian. He saw your short film this evening and he’s been watching you perform here. He’d like to talk to you.”

Almost breathless, I sank into a chair. This was Europe’s greatest director. To be given the “Lubitsch touch” meant stardom. Mr. Lubitsch looked at me. Then he removed his cigar and said in a thick German accent: “How would you like to go to Hollywood?”

I found my tongue. “I’d love to!” For a moment I thought melodramatically—it means leaving Leo, but I must choose quickly between love and a career.

Lubitsch pulled reflectively at his cigar. “I am making Mr. Chevalier’s picture, ‘The Love Parade.’ I think you would be good in it.”

Me, play opposite Chevalier? “Oh, Mr. Lubitsch!” I gasped.

On the ground that my Hollywood experience would enhance my value later, Earl Carroll gave up an option he had on my services. Paramount signed me to a seven-year contract: $600 a week for the first six months, $750 for the next six, then $1,000 a week, then $1,500, then $2,000 and, in three years, $3,200 a week!

Chevalier was on the same Super-Chief that took Mother and me to the West Coast, but I worshipped him from afar. I dared not approach him. I only dreamed of the great love scenes he and I would play under Lubitsch’s magic direction. My heart was breaking a little for Leo—and when I was not wandering through the train hoping to catch a glimpse of Chevalier, I was writing tearful letters to Leo.

The publicity drums began booming. I posed for photographs in net stockings and the highest of heels, and with a garter peeping out from the ruffles. This was the same star buildup the studio had given Clara Bow and Nancy Carroll before me.

Mr. Lubitsch greeted me with a smile when I arrived on the set. There, before my awestruck gaze, was Maurice Chevalier, the beautiful Jeanette MacDonald, and a little man with expressive, merry eyes, Lupino Lane, a British actor.

Mr. Lubitsch introduced me. “Do you remember me?” I ventured to ask Chevalier. “I worked with you in the Frolics.”

He flashed his inimitable smile. “Of course—I remember—how could I forget?”

Lubitsch passed out copies of the script. “Now, will you please sit there, Mr. Chevalier—” He pointed to a bench. “And Miss MacDonald—” He stopped. Script in hand, I was floating ecstatically toward Chevalier’s bench.

“No, Miss Roth. I want you to sit on the other bench with Mr. Lane. You’re playing opposite him.”

I was crestfallen. How naive could I have been? Who else but lovely Jeanette MacDonald would play opposite Chevalier? And I—and Mr. Lane—what were we to do?

I soon found out.

“We have two identical sets here,” Lubitsch explained. “Mr. Chevalier and Miss MacDonald will sit on that bench. You, Miss Roth, will sit with Mr. Lane on this bench. He is Mr. Chevalier’s butler. You are playing the maid to Miss MacDonald’s princess. They are having a love affair; you and Mr. Lane are having one, too. You two are to parody everything your master and mistress do. When they kiss, you kiss. When Mr. Chevalier declares his love for Miss MacDonald, Mr. Lane will declare his love for you. Get it?”

I got it. As Chevalier pursued Jeanette, at a high point in the scene, Lupino was to pursue me, bringing his face so close to mine that I was to gaze cross-eyed with love at him.

I had to hold back my tears as Lubitsch sketched the ridiculous role I was to play. But I went through my lines.

Lubitsch chewed savagely at his cigar. He began to whistle under his breath. “That’s terrible, Lillian! Where’s all that zip and zoom you had on the Ziegfeld roof?”

“Oh, Mr. Lubitsch,” I wailed. “I’m so disappointed! I thought I was going to play the love interest opposite Mr. Chevalier. I’m not a comedienne!”

He put his cigar back into his mouth grimly. “When I am finished with you young lady, you will be. Get off that bench.” I obeyed. He sat down next to Lupino Lane. “Now, Lillian, watch!” He clasped his arms passionately around Lupino, and cigar in mouth, looked at him with such soulful cross-eyes that the entire company roared.

“That’s the way to do it!” he growled. “Come here a minute.” I walked up to him. “Let’s see you cross your eyes.” I tried, unsuccessfully. He put his forefinger a few inches in front of my nose. “Watch it,” he ordered. “Don’t take your eyes off it.” Slowly he brought his finger nearer and nearer the bridge of my nose, until it was an inch away. I felt my eyes move inward: I stared, cross-eyed.

“Perfect, little lady!” he said, and chucked me under the chin. “Now sit down and make love!”

Chevalier was extremely kind to me during those delirious, free-wheeling early days. Sometime later I went to San Francisco for a film premiere. Gary Cooper, then ev

en more silent and taciturn than he is today, was my escort.

At dinner after the show I found myself seated between Chevalier and Cooper. I sat stiffly between the two men, still very much in awe of the great French entertainer. All at once I felt something against my left knee. The table leg, I thought, and I moved my leg— and the table leg moved. I blushed, and looked up. Chevalier was grinning at me. He’d been nudging me with his knee. “Would you like to dance?” he asked.

For an ecstatic three minutes I was in his arms. I cudgelled my brain for scintillating conversation, but nothing came. The best I could manage was, “Wasn’t the audience enthusiastic tonight?”

He nodded: “And you are enthusiastic, too?”

“Oh, yes,” I sighed. “I get pleasure out of everything.”

We danced in silence for a moment. “You have very beautiful eyes, Miss Roth,” he said, and his smile made my heart pound. “You must be careful that they do not get you into trouble.”

That was my romance with Maurice Chevalier.

Shortly after I signed at Paramount a German actress arrived—Marlene Dietrich. She was lonely and unhappy. We shared the same make-up girl—Dot Pondell—who years later became Judy Garland’s confidante. It was Dot who was always after me to take off weight, just as M-G-M nagged at Judy for her plumpness. I gained weight as we shot “The Love Parade” and Lubitsch ordered me to take off ten pounds. I wasn’t too successful; and since he shot the story backward, I was heavier at the beginning of the picture than at the end. I tried every method to lose weight, even gathering courage one day to accost one of Paramount’s top stars who seemed to be able to melt pounds away at will.

“How do you do it?” I asked. “What’s your secret?”

“No secret at all, Lillian,” she said. “Just take a glass of half-and-half—half gin, half lemon juice—every morning for breakfast.” Her method was far too drastic for me then. (Years later I tried the plan, improving on it by eliminating the lemon juice, but then the idea had nothing to do with diet.)

One morning Dot said, “Why don’t you drop in on Marlene? She’d appreciate a visitor.” I went to her dressing room, and whether because of my youth or my obvious hero worship, she confided in me. She was unhappy in Hollywood, she said, lost in the swift, impersonal rush of America, and heartsick for her little daughter, whom she had left in Germany. I adored Dietrich, her charm, her deep voice, her warmth. As we chatted, I surreptitiously glanced at her legs again and again, for she was to be my competition: according to Paramount publicity, I had the most beautiful legs in Hollywood. This was not actually true: Lubitsch nurtured the legend by ordering me to wear shoes and hose of the same color, and coaching me how to walk and place my legs when I stood or sat. Dietrich never worried about such details—no matter how she walked or sat or stood, her legs were beautiful.

I was not too happy myself in Hollywood. My social life was dull. Letters to Leo every few days; now and then one to Ann, who was attending boarding school, and to Dad, who was living in Boston; the movies with my mother, when I wasn’t too tired; a visit or two. with Mr. Lasky, who had moved to the West Coast offices of Paramount. My hours were long. Sometimes I began work at 6 a.m., when I had to be on set for makeup, and returned home after midnight. I went out a few times with Junior Laemmle, now a producer at Universal. I was working too hard to be out much, or to indulge in any of the wild Hollywood life I’d read about Nothing had much meaning until David came along.

CHAPTER VII

I HAD only a waving acquaintance with David Lyons at Clark, I was fourteen, then, and he was nineteen. But he was to become important to me during those first few months in Hollywood.

Junior Laemmle phoned me one night and asked me to go for a drive. On the way he said, “I forgot to tell you—you know, we’ve got a school friend living over in North Hollywood. He’s been under the weather lately, but I know he’d like us to stop in and say hello.”

David sat up in bed when we walked into his room. His curly blue-black hair was tousled, and he was pale, but he flashed a cheerful, contagious grin that had me smiling back without realizing it. “Hiya, Lums!”

“What a funny name,” I said. “Nobody ever called me Lums.”

“That’s short for Lillums,” he said. “And Lums sort of fits you, too.”

“My name’s Lillian,” I said a little tartly. “My mother always said everybody must call me by my full name, Lillian. Not Lilly. And not Lums.”

His smile lit up the room. “Well, I’m sorry, but you’re Lums to me. Now, if you’ll just skidaddle out of here and wait a minute, I’ll get some clothes on and we’ll talk about school days.”

When he came into the living room a few minutes later and draped his slim, five-foot-ten over the arm of my chair, I began thinking that perhaps Leo wasn’t the only boy in the world. David was brimful of personality, and exuded charm and good spirits—an exuberance you could not withstand. He was working for Junior as an assistant director, having recently come from a six-month stay in Arizona.

We talked about Leo, whom he knew and liked, and about Clark.

“You used to be standoffish, if I remember,” I said. “You drove a big yellow Packard—”

“And I wore a raccoon coat—”

“That’s right,” I said, suddenly remembering the dashing appearance he made, and how I had been too shy to try to know him better because he was so much older. “And you were going to study law.”

He nodded. “I went to Syracuse University. But now I’m out here—and at this particular moment,” he said, looking at me meaningfully, “I don’t mind telling you I wouldn’t change for anything.”

I must have raised my eyebrows at that, for he hastened to add, “Look, Lums, don’t get me wrong. I feel toward you like I would toward a sister. I know you go with Leo, but suppose you were my sister. You’d let me take you to a movie, wouldn’t you?”

I nodded.

“Well, believe me, that’s the way I feel about you. And I’d like to take you out tomorrow night. May I?”

He might get off his high horse and feel about me as a boy feels about a girl, I thought, a little annoyed. But I welcomed his friendship. I was in glamorous Hollywood, and nothing particularly glamorous was happening to me.

A few nights later David took me to the opening of Junior’s first picture, which starred Alberta Vaughan. “Now, you’ll be brought to the mike and asked to say a few words about Junior,” David warned me. “After all, you’re going to appear in ‘The Love Parade’ and you’re a personality.”

I planned to say how glad I was to be there. Instead, I began talking about Junior’s activities at school, and went on until David all but pulled me away. I had made a fool of myself.

David sought to console me during the ride home. “I feel about you as I do about my sister” he said, “and if she were sad, I would do this.” He pressed a cool kiss on my forehead. That irked me. The more often he called me his sister, the more annoyed I became—and the easier it was to forget Leo.

My letters to Leo became fewer: his answers to me, more infrequent. Soon David and I were meeting wherever possible. It wasn’t always easy, because Hollywood’s infamous caste system kept us apart. The studio insisted that I was a star, and ought not be seen too often with David, for he was only an assistant director. Thus, he was never invited to the studio parties to which I was asked, although those who extended the invitations knew we were going together. David took it in good spirit. He always waited outside until the party was over, and then we had a little time to ourselves. The nightlife we knew consisted of a brief visit to BBB’s, a nightspot off Hollywood Boulevard, where we sipped soft drinks, or a dance at the Roosevelt Hotel.

“I don’t feel at all about you as I do about my sister,” he finally confessed. “But I don’t want to be a heel taking away another fellow’s girl.”

I reassured him. “That’s over now. You’re not taking me from Leo. My romance with him was puppy love, David. I know it now. I

t’s the real thing with you.”

“‘Lums, darling,” he would say. “If you only knew how much I love you and how happy I want to make you!” He would kiss me then, and I would forget everything else. Only with David, it seemed, could I be myself. He loved me as I was. I needed no pretense, felt no need to justify myself to him. He alone spoke about making me happy; everyone else spoke about making me famous.

We began to talk about marriage. I would leave the profession when I was twenty-one; I would work hard, meanwhile, and save my money, and he would work hard, and save his money, and then we would be married:

As the weeks passed, Katie grew more and more concerned. She upbraided me. David wasn’t the right boy, she said. Anyone who would allow me to give up my career couldn’t really have my interests at heart. In any case, at eighteen what right had I to contemplate marriage? I was only at the beginning of a career that could take me to unknown heights. “Oh,” she cried, “when I think of the youth and beauty and talent you’re ready to throw away for that boy—.” She grew hysterical. “I can’t bear to see it,” she wept. “If he must be with you all the time, take another apartment. I just can’t bear to see him around you all the time!”

I was torn. Everything Katie had built up for me, all the dreams she had had for me even before I was born, were crashing before her eyes. And she was right: I was too young to think of marriage. But to turn away from the one person who made me feel whole—I didn’t know what to do. The headaches that tortured me in “Artists and Models” came back. I had never disobeyed Katie….

I'll Cry Tomorrrow

I'll Cry Tomorrrow