- Home

- Roth, Lillian;

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Page 25

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Read online

Page 25

Mr. Benson was silent for a moment. Then he said earnestly:

“Please, please do think it over, Mrs. McGuire. There are instruments in the Lord’s work, and you may well have been chosen to be such an instrument. The criticism you may receive from a small minority must be measured against the help you will give to countless others who hear you.”

I agreed, finally, and Burt with me.

We spoke, not of ourselves but of alcoholics: of the 5,000,000 and more in America out of a population of 160,000,000. We cited the grim statistics: five per cent of all persons who drank were alcoholics. At least 12,000 died annually of alcoholism, but the true mortality figure was many times larger, for heart attacks were usually given as the cause of death because of the wholly unjust stigma attached to alcoholism. We pointed out that alcoholism was no respecter of persons: social registerites and laborers, Senators and members of Parliament, princes and paupers, high bottom or low bottom drunks—all were as one.

We told of the National Foundation for Alcoholism which provided hospitalization for alcoholics. We paid tribute to Marty Mann, citing her long, successful struggle to have legislators recognize alcoholism as a disease.

The results were staggering. We were inundated with hundreds of telegrams, letters and invitations to speak. Alcoholics converged upon our stage door. As long a line waited there as waited outside the Tivoli Theatre box-office in front But in the queue backstage there were weeping mothers and wives, sometimes entire families, praying that we could help their sons and husbands.

From waking to sleeping we had no rest, either at the theatre or our hotel. We made appointments at seven a.m. and at two a.m. the following morning. We talked with men and women in our dressing room, in clubs, in private homes. And one morning another minister approached us—the Rev. Gordon Powell, of Melbourne’s Independent Church. He would be deeply indebted if we would speak at his church: but he wanted something more than statistics. I must speak out of my experience and out of my heart. He pushed aside my doubts. Finally I agreed: and since it was evident we could no longer handle both stage work and alcoholics, I took a three-week leave from the theatre.

When we arrived Sunday morning at Independent Church, and were seated on either side of the altar, Dr. Powell introduced us, saying that we were giving away what God had given to us. No woman had ever spoken from his pulpit before, but one would today. His introduction was eloquent and moving.

I was deeply affected. The infinitely peaceful atmosphere of the church, the majestic organ music, the tenderness and sincerity of Dr. Powell’s words…It is a difficult thing to express, but a profound sense of the religious came upon me. I thought, I wonder what God wants me to say.

I had no notes. I was not a public speaker. I had a limited education. What was I to say to these people? As I stood before them, I prayed silently, “God, please put the words in my mouth.” And the words came.

When I finished, I saw tears in the eyes of many in the front pews. And Dr. Powell, moving slowly forward to the pulpit, turned and gave his blessing to me, and to Burt, and to all in the church.

I returned to the hotel tremendously moved. I felt I had a soul, that it was reaching forward to the unknown, not a dark, frightening unknown, but a warm, friendly otherworld. I was elated, yet serene. Burt sat in a chair and began to read. I threw myself on the bed, tinned on the radio next to me, and tried to relax.

I closed my eyes. The BBC, from London, was broadcasting a presentation of Our Lady of Fatima, relating the story of how she appeared to three shepherd children in Portugal, on a Sunday morning in the last year of World War I, while all the world prayed for peace, and revealed to them things that were to come. The narrator’s voice was soft, his words eloquent, and I listened.

No one believed the children. Instead, the Mayor ordered them to jail as punishment, and refused permission for them to go to the grotto where the Lady promised she would reappear and speak to them again, and cause a miracle so non-believers would believe.

Thousands flocked to the grotto. And a miracle did come to pass. It was attested by correspondents from anti-religious newspapers who came to scoff. Some had seen one thing, others had seen other things, but all had seen something not explainable in ordinary ways. Those who were religious saw the Infant Jesus on the lap of Mary. Some saw the Blessed Mother. Some gazed without hurt directly into the molten, whirling core of the sun, which spun and danced on its axis, then hurtled toward the earth, then halted midway. It poured rain, and yet none were wet. And again and again, month after month, Strange events took place in the grotto where the shepherd children first saw the Lady of Fatima.

A great hope took hold of me. If God had allowed the Blessed Mother to appear, it meant that every loved one who had died, still continued on: for surely if He allowed one to exist, He must allow all to exist It proved the promise in the Bible: I shall give you life eternal. God surely must love what He creates, as a father loves his children. Many thoughts went through my mind. I thought of my father, and the understanding I could have given him and did not, because I did not understand alcoholism until I suffered from it myself. But here was hope. He knew I was sorry. Here was an answer. There was eternity. Human struggling and suffering were not for nought…

“Oh, Burt,” I said, almost dreamily. “That story rings so true to me. It must be wonderful to be a Catholic and have such strong beliefs. I’d like to know more about Catholicism.”

My words must have sounded startling to him, spoken without warning, although he knew I believed in God, though I had found no spiritual contact with Him.

After a moment, Burt said quietly, “Well, you know Lillian, it takes a long time to study Catholic doctrine, and it’s not easy.”

“I know,” I said, thinking aloud rather than speaking the words. “But I must try. I won’t be satisfied until I do. I’ve been searching for a long time—maybe this is what I’ve been searching for. Maybe,” I added, “if I found a Jew who understood Christianity or a Christian who understood Judaism, it might clarify my thinking.”

Burt rose and walked slowly to the window. “It’s odd that you should speak of a Jew who understands Christianity,” he remarked. “As a boy I was taught my catechism by a priest who was born a Jew. Mother told me later he’d gone to Australia.” He paused. “Australia’s a big country, and Lord knows where he is—”

He began to thumb through the telephone book on the stand between our beds. “If I recall, he was in the Order of the Blessed Sacrament,” he said, almost to himself. He found the page listing churches: there was a listing for Blessed Sacrament Church. He rang the number. I heard him speak into the mouthpiece. “I knew a priest in America many years ago who came to Australia,” he said. “He’d be quite an old man now. Do you suppose you would know where I might find him? His name was Father William Fox.”

He listened for a moment, then slowly replaced the receiver.

“Father William Fox is a priest in the church I just called,” he said, in a strained voice. “It’s three blocks from here.”

Father Fox was a tall, thin stooped man with warm brown eyes and a gentleness that won me to him at once. Burt explained the strange coincidences which led us to his study.

“Sit down, my child,” the priest said to me. “What is it you want to know?”

I felt utterly inadequate to answer him as I wanted to. I was on the edge of an awakening which I sensed, or experienced, rather than understood. But I tried to reply.

“Father, there’s so much I want to know! But I’m really confused. There’s something in me urging me to break through, telling me that there is something to be known, a great truth—and I’m frightened of it.”

“Frightened of what?” he asked gently.

I searched for words. “I guess, just frightened of consequences. I love my people, but what will they think of me if I turn to Christianity? Will they think that I am disowning my birthright as a Jew? On the other hand, will Christians think I’m trying to es

cape persecution by hiding behind Christianity?” I spoke as honestly as I knew how. “But I do have this feeling, this yearning, and I must find out what it is.”

Father Fox shook his head slowly, and smiled. “Patience, Lillian, patience. It is wonderful that you feel you want to become a Catholic, but you must know it. Feeling is emotion: knowing is logic. For truth’s sake, you must not worry about the consequences or what people think. If they love you, they will love you no matter what your faith. It’s only important to know what God wants of you.”

“But how would I know?”

He said, “Pray to Him. Pray to God. He will direct you in His own good time.”

Before I left, he told me: “Remember, Lillian, you can be proud of your heritage. For Christ was a Jew. Judaism is the trunk of the tree, Christianity the branch. I advise you to pray—and wait.”

We departed, with a promise to attend Sunday Mass.

“What does he mean, I will be directed in God’s good time?” I asked Burt as we walked out. “There are so many things I want to know. How will I go about it? Is prayer the way?”

Many people, Burt said, had read their way into the Church. But prayer was important, too. Prayer opened a door for them. It might open a door for me.

As we passed through the foyer of the church, I took from the Readers’ Shelf a number of pamphlets. When we returned to our hotel, I said a little prayer to God.

“I don’t know what You want from me, Dear God, but I hope that as the Jews in the Bible asked for a sign, You will give me one so that I will know what to do when the time comes.”

I prayed, not quite sure what I was asking for, but I prayed as Father Fox had told me to.

Next morning the telephone rang. It was the desk clerk. “There’s a parcel down here for you from America. Shall I send it up?”

When I opened it, I found two copies of Our Lady of Fatima. They had been sent by Burt’s mother, one for each of us. They had been mailed two weeks before.

Had I been given a sign?

CHAPTER XXVI

WE HAD many talks with Father Fox. He was extremely interested in the interpretations of AA written by ministers in the United States, which we had brought along with us, and particularly one brochure published by a Catholic priest which called attention to the similarity between the Twelve Steps of AA and the Fourteen Points of St. Ignatius.

Both stressed turning your will over to God; confiding in another; making amends; and helping others. Father Fox had hundreds of reprints made, to be distributed in the Catholic churches of Australia. He also arranged for Burt to meet with a group of priests so that he could speak to them on AA. They, in turn, would discuss the subject from their pulpits.

What especially pleased us was to learn that the Rev. Gordon Powell and Father Fox—distinguished Protestant and distinguished Catholic men of the cloth—had met, and now worked together to help alcoholics.

Our days were crowded with speeches. One of our talks was made before the Australian Society of Psychiatrists, which invited us to address its annual convention in Melbourne. Dr. Powell introduced us.

Many in the audience were critical. They doubted the efficacy of the Twelve Steps. They doubted the success of AA. One man stood up and demanded:

“Miss Roth, have you had special training in psychiatry?”

“No, sir,” I said.

“Do you have a degree in psychology or related subjects?”

I shook my head.

“As a matter of fact,” he went on, “you have no university degree of any kind from any recognized institution?”

For a moment I was tempted to say, “Bloomingdale’s,” but this was not the occasion.

“As a matter of fact,” I replied, “I never went to college. My formal education ended when I was fifteen.”

There was a moment of silence, then cries of “Hear! Hear!” and applause.

Dr. Powell closed the meeting. “I hope that you will all keep us of AA in mind when you deal with patients who may need the help and counsel of an organization like AA,” he concluded.

At the invitation of a group of Methodist ministers in Adelaide, we flew there, where we spoke to the Mayor, members of the City Council, and the Director of Prisons. I made clear that we spoke not as AA representatives, but only as alcoholics whose cases had been arrested.

One evening an intense young man came to me as I left the platform. “I’m a newspaperman, Miss Roth. Could I speak to you in your room?” We invited him up.

He asked many questions, thanked us and departed.

Next morning a special delivery letter arrived. It was from our friend of the night before. He was not a reporter: he was a printer, and an alcoholic. He was on the verge of committing suicide, he wrote, when he had spoken to us. All he wanted now was our forgiveness. Would we telephone him and let him see us once more?

A few hours later he was in our room again.

“I’m a fallen-away Catholic,” he began. “I find it hard to believe in God.”

I told him I could not help him in this. I was still in search myself. And my husband, I said, had been away from his church since childhood. But why could he not believe in God, I asked?

“I was a flyer in the war” our visitor said. “I was assigned to bomb a schoolhouse—a retaliation raid. I dropped my bombs while the children played in the yard. That was my order, and I carried it out.”

As he zoomed away, he looked behind. He held his hands over his eyes as he spoke. “It’s haunted me. Never, to my dying day, will I believe in God again, nor will I be able to erase the sight of those children—what I did, knowingly.”

I racked my brains for the right words to comfort him. What could I tell him? I could say only that all of us may be chosen as instruments in ways we cannot understand. “You came to me for help,” I went on. “Perhaps I can’t help you as I should. But I need your help. I have a little book on the Mass. I don’t understand it. Even if you don’t believe any more, won’t you explain it to me?”

So we sat that night. He did not drink. He explained the Mass to me. These, he said, were the psalms of David. I had not known that. And this was taken from the Jewish Passover service: the breaking of the bread, the drinking of the wine. As he expounded, earnestly and with increasing calm, I thought: now we three have something in common. He and Burt were not attending their church, yet they were helping me, a non-Catholic, to understand their faith. By the same token, Burt and I had his trust.

When we left Adelaide, he was using his presses to reprint AA literature, and working with local clergymen to organize an ex-alcoholics group there.

In Brisbane, an attorney, a taxi-driver and an actor formed the first nucleus of ex-alcoholics to carry on the work we began in that city.

Katie’s letters, which had been following us, caught up with us at our final stop, Sydney. They were letters of love and encouragement, full of homey gossip. Once I had told her of Burt’s wild dream that I would “speak in churches.” Now she reminded me of it.

One of my last talks was in North Sydney. A Jesuit priest, who introduced himself as Father Richard Murphy, chatted with me when I finished. “There was something universal about your talk,” he said. “But if you will forgive me—you seemed a bit uncertain as to the spiritual aspects of your struggle.” He looked thoughtfully at me. “When I said ‘universal,’ I meant universal in the sense of Catholic,” he added.

I found myself telling him what I had told Father Fox.

“If God wills it, it would be wonderful,” he said. “It would mean much to both of you if you could be married in the Church.”

He suggested that I read “Faith of Our Fathers,” by Cardinal Newman who, he said, was a convert. We had long talks on faith and God.

Before we left Sydney, Burt and I were invited to visit the prisons. We were shocked to see that alcoholics were jailed in the same cell blocks with murderers, and locked behind iron doors from four p.m. until six a.m. “They don’t understand how cruel

that is,” I explained to our guide. “An alcoholic is a desperately lonely person. To lock him up so long is pure torture.”

We were invited to make our observations formally to the Ministers of Health, Education and Prisons. In doing so, we explained how alcoholism was handled in the majority of the States. Later we learned that more liberal methods of treatment were introduced in Australia.

Our last tea in Sydney saw us as guests of the warden of the women’s prison. We chatted in friendly fashion. A pretty, apple-cheeked girl, wearing a tiny apron, served me my tea, asked me charmingly if I took milk or sugar, and deftly presented me with napkin and muffins.

“Is she one of the prisoners?” I asked when she was out of hearing. “She seems so lovely and sweet.”

The warden smiled.

“Oh, yes,” he said. “An excellent prisoner, too.”

“What did she do? What is she in here for?”

The warden looked at me for a moment. “She poisoned her husband,” he said blandly. “She put arsenic in his tea.”

I must have set my tea down sharply, for it spilled over.

We had now been away from home for eight months— the longest period Katie and I had yet been separated. I longed to see her. We wired her money to meet us in Los Angeles, and in May, 1948, we returned to the States.

On the boat Burt and I had time to look through hundreds of letters that had come to us from all parts of Australia, from churchmen, from leaders of missions, from men who had campaigned, as they put it, “against John Barleycorn” all their lives. There were reports on alcoholics who had been helped by AA, notations which summarized so much in so little:

“Percival started on a job at the shoestore Friday last He’s really on the beam now.”

And again:

“Have I written you about Stan Lewis? He was the advertising fellow from Auckland, who got the shakes the night Lillian spoke. Well, you wouldn’t know him today. He’s chairman of his group, and he’s been sober for a month straight—the first time in years.”

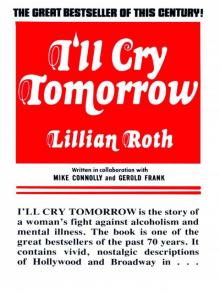

I'll Cry Tomorrrow

I'll Cry Tomorrrow