- Home

- Roth, Lillian;

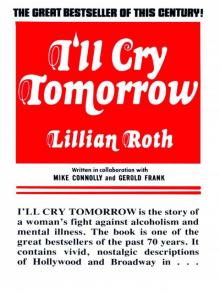

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Page 19

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Read online

Page 19

The orange phase passed: in its stead, I lusted for gum. I was insatiable, and five sticks at a time in my mouth only whetted my hunger for them. Yet I was beginning to relish the taste of food, something I had almost forgotten.

One Sunday rest period I was allowed for the first time, to look through the New York Times, one of the few newspapers permitted in the institution. A story related the experiences of Mrs. Marty Mann, Director of the National Foundation for Research on Alcoholism. An alcoholic, she had been in and out of hospitals. Many doctors tried futilely to aid her. She attempted suicide once, and actually jumped—living to tell the story of how she achieved sobriety through Alcoholics Anonymous, a group of ex-drinkers who had their own methods for keeping themselves from liquor.

Panic seized me. I had been tricked! If doctors hadn’t helped Marty Mann, if institutions hadn’t helped her, what was the good of me being locked up here? I felt like a caged animal. My heart beat so wildly I thought my chest would burst Four more months to go—maybe more?

Next morning I showed the paper to Dr. Head. “Read this!”

“Lillian,” he said, after glancing at it, “we know about this. Alcoholics Anonymous is not for you—at present. You are a sick girl mentally and physically. You would be unable to understand their therapy at this time; you would fight it. Our principle job right now is to build you up physically and to teach you how to live for a long time without alcohol.”

My liver was permanently damaged, he went on. I could be healed to a considerable degree. “But you cannot be impatient,” he said. “You are not ready for the world, and the world at the moment does not want you. But—” he smiled, and took my hand, “they will, believe me, they will.”

That night I searched among my possessions until I found the small leather Bible Estelle Demarest had given me. Dr. Head had kept it the first two weeks. “We had to be sure you weren’t suffering from a religious mania,” he had said. I fell asleep reading it.

The day came when Katie was permitted to visit me alone. A long hill led from the bus stop to the hospital gates. I waited outside for her. She could not afford a cab, and I watched her laboring up the hill. She arrived, panting and out of breath. I wanted to cry. Yet, before she left some perverse impulse made me fling at her, “It’s your fault I’m here. God damn it, you ruined my life! If it hadn’t been for you, I wouldn’t be here, because nobody wanted me, that’s why I’m here!”

She stared at me, fighting hard not to cry; and after a little while, she turned and left.

I sobbed to Dr. Head: “Why did I treat her that way?”

Sometime in the night, time became telescoped. I was six years old….

“Lilly, baby,” my mother said, warmth and expectation in her voice, “we’re going over to Uncle Jack’s and you can pick out a little coat for yourself. You’re going to be the best-dressed little girl in the neighborhood.”

Uncle Jack had a drygoods store under the 2nd Avenue EL When we walked into his apartment above the store, he was hugging and kissing his wife. “They’ve just been married,” my mother whispered. I had never seen her and daddy hugging and kissing. I felt strange.

Uncle Jack turned to me gaily, picked me up and threw me into the air. “What can we do for you, sweetheart?” he asked.

“I want Lillian to pick out a coat all by herself,” Katie said.

“Righto!” he said. He turned to his wife. “Pearl, do you want to come along? Lillian is going to pick out her own coat.” We went downstairs and he placed two velvet coats before me, one blue, one purple.

“Let her have whichever one she wants,” said my mother. “She’s the boss.”

I liked the blue coat. But I thought, no, I better not take it. I said, “I’ll take the purple coat.”

“You sure that’s the one you like?” Katie asked.

“Do you like it, Mommy?”

“Whichever one you like, I like.”

“Well, I’ll take the purple one,” I told my uncle. As he wrapped it, I felt wretched. It wasn’t the color I really wanted. I took it because I felt that my mother would not like the one I chose, if I chose the one I liked.

What was my fear? That her face might reveal fleeting disapproval? Was it that I would rather endure anything than surprise a look of pain on her face? Why did her pain, however small, strike into my very being?

And then I was awake, in a bed in Bloomingdale’s, an institution for the mentally sick, weeping for my mother…

I tried to explain to Dr. Head.

“We’re so close,” I said. “Maybe it’s our sense of humor, but in our most tragic moments, it seems we can laugh together. Maybe we’re near tears when we laugh, but…It’s hard to put into words. We’ll be at a party, and something will strike us simultaneously as roaringly funny, and we’ll grow hysterical laughing together. Then we’ll be ruined for the evening, because each time our eyes meet we begin laughing all over again. It’s this laughter we have, this closeness between us, as if we were one person—no matter how bad a thing becomes, it’s never too awful if we have each other.”

“Yes,” he said. “Your mother is your real love.”

Perhaps it might help if I saw Ann, I suggested. We had had little to do with each other in recent years, and Katie had kept from her as long as possible the serious nature of my illness.

She came up with Katie. I had asked Ann to bring me paper tissues, because I cried so much that I never had a sufficient supply. “Did you bring the tissues, Ann?” I asked the very moment she came into the room. Yes, she had: she had left them downstairs at the receptionist’s desk, as directed.

I exploded. “Why? Why? It will take them three days down there before they examine them and send them up to me! I need them now! How could you do that to me!” Savagely I berated her.

Dr. Head said later: “My dear girl, when you leave here, I advise you not to live with your family because you react badly after you see them.”

Finally I was allowed off grounds accompanied by Edna and Minna for a brief visit into nearby White Plains. It was a strange experience. The streets and traffic frightened me. The faces on the street—how intense and contorted they were! I realized why. I had become so accustomed to the apathetic faces about me in Bloomingdale’s.

“Let’s have some coffee,” Minna suggested. We entered a restaurant. As though in a dream, a tray of martinis materialized and floated by me: a waitress, threading through the crowd, held it high, balanced on one hand. My eyes fixed on the martinis and followed them as though I had been hypnotized. The tray was lowered and placed on a table before three women. They lifted the glasses to their lips, and drank: and I drank with them. I felt the dry tart taste going through my nose, I tasted the acrid bitterness of the olive, and I gagged. That was how it had been in the old days: even when I was hungover, my hand would not lift the drink before me, nor could I swallow: anticipation paralyzed me, and I gagged.

I fought off a choking attack until hot, black coffee came, and I forced it down, scalding my mouth and throat. Then I looked up again, at the women with their martinis. I sipped my coffee, and glanced at Edna and Minna. Did they know I still wanted a drink?

CHAPTER XXI

I WAS getting better. Proof: I was allowed to make a trip to New York by myself. It would be a test No one was to pick me up. I would do it all by myself—buy the tickets, board the train, hire a cab, go to my mother’s apartment.

The hot sun shone, and I walked slowly, wanting to cover my face, my ears, from the noises of the street, the voices of the newsstand dealers, the swirl and confusion of traffic in New York this April day, this bright sunlit Spring day.

I clutched my Bible in my hand and recited the verse to myself:

“Thou shalt not be afraid for the arrow that flyeth by day nor for the destruction that wasteth at noonday…”

I turned a corner. There before me was a liquor store the first I had seen, or been conscious of, since I had been in Bloomingdale’s. I turned my head sharp

ly away, and stared across the street until I was well past it.

A few stores further, a huge sign over the sidewalk: BAR. I shut my eyes tight and counted to 30 as I walked —time enough to pass it.

Then BAR & GRILL & RESTAURANT loomed ahead of me. Through the large window I saw men drinking beer. I jerked my head away, rushed into a drug store and ordered coffee at the counter. I drank it swiftly, because the walls were beginning to spin, and my throat to constrict.

What would happen if I take a drink? I’m an alcoholic, Dr. Head says. If I drink, it means death. What does he mean by death? Not that I will drop dead if I take one drink. Of course not. He means cirrhosis of the liver. But he had warned me—to drink again would cause insanity. That was absurd. Certainly, if I’ve been sober for four months, how can one drink drive me crazy? What had he said: “You are an alcoholic. If you drink, you will go insane. If you continue to drink, you will die. Lillian, for you to drink is to die.”

“You’re trying to scare me.” Panicky. “You mean I’ll get sick and die eventually.”

He shook his head. “No, not eventually. Soon.”

His words were still in my mind as I rang my mother’s bell.

“Lilly! You made it. And all by yourself!”

The experience was unreal. She led me into the single studio room that was now her home. She had cooked lunch for me, dishes I had always enjoyed as a child. “You look wonderful, baby,” she said. “Yes, Mom,” I said, but long before train time I glanced repeatedly at the clock. “I better go back,” ran through my head. “I haven’t anything to say to her.”

We took the train to Bloomingdale’s, slowly walked the hill to the gate, and waited silently for the nurse to unbolt the door. “I’ve brought my daughter,” said my mother, and kissed me, and held me close for a long moment, and went back alone in the dark.

Then, a weekend in New York, we visited some of mother’s friends, and later, she and I returned to her room. I thought, “When I do get out, what have we got to look forward to? We have no money. What will we do?”

We sat opposite each other, silent I burst out crying. I ran to her and sat in her lap and put my arms around her and sobbed, and as I sobbed I played with her neck and her hair, as I had done so many years ago. I was 34 years old and my mother rocked me back and forth like a little child.

I returned alone to the hospital that night. I was frightened on the way to the train. The dark began to take on shape. Again the Bible’s words ran through my brain. “Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night…”

I walked hurriedly. “Good evening.” A man was beside me, matching his step with mine, tipping his hat, smiling at me, murmuring words. I shut my ears. “Because Thou hast made the law which is my refuge…therefore shall no evil befall thee.” The man had dropped back. I was alone again. “He shall cover thee with His feathers and under His wings shall thou trust. His truth shall be thy shield and buckler.”

I thought, in the train: perhaps when God made mothers, their hearts were the shield and the buckler, and their love the wings placed over you to protect you. Had I not sat in my mother’s lap like a little girl?

Again and again, the past, the distant past, came back to me. How old was I? Two? Two and a half? Three years old? I lay, half asleep, in a back bedroom, in a house in Boston. There was a living room, and the bedroom beyond, separated by a draw curtain. In the bedroom lit by a yellow gas jet on the wall, my mother stood before the mirror, putting on a great hat with big yellow feathers. She wore a tight black skirt, but such a pretty skirt, with a large white blouse. What a small waist my mother has, what a tiny little waist, I thought.

I watched the shadow of my mother on the wall, and then she was bending over and kissing me, and then she was not there and the shadow was gone and the gas jet burned alone and I did not like the feeling in the room at all…

“Don’t you think you might go back to show business?” Dr. Head asked.

“Why would anyone want to hear a drunk like me?”

Dr. Head looked at me rebukingly. “I think you ought to stop thinking of yourself like that,” he said. “You haven’t had a drink for more than five months. Isn’t that true?”

I nodded. Nobody could take that from me.

He thought for a moment “Are you jealous of anyone in your profession?” he asked suddenly.

It was a chance shot, but it struck home. Jealous? Not exactly jealous, but I—well—I envied Ethel Merman. All at once I was aware how deeply it had rankled in me. “When I was in lights,” I said, “she was a stenographer and she often came to the Paramount to watch me work. A friend once took me to hear her sing. She was singing professionally then, and soon became well known. She did numbers I did, and made shorts, too.” I was silent Then the words burst from me. “Why, Dr. Head, when I watched her do songs like ‘Sing, You Sinners!’ I thought I was watching myself.”

Dr. Head nodded. “Go on.”

“I wondered why she sang that number so often. She had every right, but, well-I didn’t like it. She had a wonderful way of putting a number across, and she had a magnificent brassy quality. I admired her. One year she did a Broadway musical. I was cast to play the same role in the film. The director said, ‘My, Lillian, you’re using a lot of Merman’s mannerisms.’ I said, ‘Well, if you look up a picture called “Honey,” in which I sang “Sing, You Sinners!,” you’ll find that I always used those mannerisms.’”

I remembered more. There had been the summer of 1935 when I was married to the judge, drinking too much, unhappy and seeking ways to keep busy. Paramount screen-tested me for a musical, liked the test, and went so far as to draw up contracts for me. This was to be my great chance… And suddenly Ethel, who had been busy on another picture, was free, and Paramount signed her instead.

“I remembered thinking then, ‘This girl has taken my place. We’re so alike in our delivery.’ I lost my desire to make a comeback. I was miserable in my marriage, and when I turned to escape in the one thing I knew—my profession—people would think me an imitator. I was trapped. All I wanted then, when my marriage broke up, was to earn a little money…”

And Ethel haunted me. Every engagement I played on that long road which took me to this room in which I now sat, people said, “You know, you sound so much like Ethel Merman!” It had become too difficult, too embarrassing to explain. “Ethel was now one of our great stars, as she deserved to be,” I said.

“Then you were jealous of her?”

Jealous? No. That wasn’t the right word. “But as I saw her success, I saw what I had thrown away. Looking up from the depths of my alcoholic shame, she represented what I might have been.”

“Don’t you know that you can be a headliner again?” Dr. Head asked gently. “And in your own way, so you won’t be compared to her?”

“No. People will always say I’m a carbon copy of someone else. If I can’t be me, what can I be?”

Dr. Head sat back thoughtfully. “When you go to the city on your next visit, why not look up an accompanist and rehearse a few new songs? You can practice your lyrics here. Maybe that will be an outlet for you. I’m sure it will make your mother happy, too.”

Katie made the arrangements. She told my former accompanist, Helen Stevens, that I was “coming in from the country, and wanted to learn a few numbers.”

Helen was kindness itself when I came to her the following weekend. The first song she gave me, however, was “They Say Falling in Love is Wonderful.” It had been made famous by Ethel Merman. “Helen,” I said, “That’s Ethel Merman’s number and I just can’t do it They’ll say I’m copying her.”

“Nonsense,” Helen snorted. “You’ll have your own interpretation. You ought to learn it—it’s the popular number of the day.”

I rehearsed it, and “J’attendrai,” and “If This Is But A Dream, I Hope I Never Wake Up.”

When our session was over, I offered Helen a ten dollar bill which Katie had put into my purse for the purpose Helen pushed the

money aside. “Don’t be silly,” she said. “You’ve overpaid me in the past. I’m not taking money from you.”

For a moment I flushed. How much did Helen know? How much could Katie have divulged? But Helen was an old friend. I could trust her.

“See you next Saturday,” she said, and kissed me.

I hummed “J’attendrai” on the train back to Bloomingdale’s. Would I ever face an audience again?

Then, suddenly, six months had passed, and almost before I knew it, Dr. Head was bidding me goodbye.

He had a few words of caution. I should get to work as quickly as possible. Avoid people and situations likely to upset me. “Your first six months outside will be tougher than the six months here,” he said. “Remember when you told me that the people you saw on the streets outside seemed tense and anxious, and those here calm and placid? That’s because our people here have security and protection. They’re kept from shocks and hard knocks. Outside you’ll be thrown into noise and confusion, you’ll be jostled, people won’t treat you with kid gloves because they won’t know what you’ve gone through. You’ll be upset emotionally and you’ll want to drink. You’ll meet people who will offer you liquor. It will be only an arm’s length away from you all the time. You should know all this, and be prepared.”

He paused. “Remember, for you to drink is to die”

He gave me a box of seconal sleeping pills for my first few nights. “Don’t make a habit of these,” he warned me. “And keep in touch with me, Lillian. I’ll be able to give you support if the going gets too hard. But try to stand on your own two feet as long as possible. You can do it.”

I was free.

CHAPTER XXII

I'll Cry Tomorrrow

I'll Cry Tomorrrow