- Home

- Roth, Lillian;

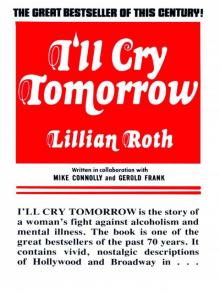

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Page 13

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Read online

Page 13

I stood over him, almost beside myself with disappointment and anger. How could I stay sober if I couldn’t count on him? What a mockery the picture he had painted—Mark and me and Sonny! Anger rose in me. “Get out!” I suddenly screamed. “You can’t be trusted—get out of here. I don’t want a drunken bum staying in my apartment all night. Get out! My mother was right—” I pulled at him.

He rose swayingly and took a step forward. Suddenly his fist exploded in my face. My head rocked and I felt a sharp stab of pain; a pinwheel of flame whirled in my eyes.

Next thing I knew I was laying on the bed. There was blood over me and the bed, and the wall was splashed with it “My face,” I moaned. “My face.” My lower jaw was hanging, swinging back and forth.

The telephone rang. I looked about, dazed. Mark answered, his voice smooth as butter. “Hello, Linda. She’s fine, thanks. Yes, we’ll try to make it.”

I was half conscious, my face numb. “Your jaw is broken,” the doctor was saying. I sat in his office for hours until he completed wiring my jaw. “You won’t be able to open your mouth for six weeks,” he said. “You’ll have to live on liquids.”

The next days were an unreal phantasmagoria, Ruth Bernstein and her husband, Bernie, found me in my apartment, passed out. I had been drinking steadily for five days. She took me to the hospital, where I was fed through a tube. The doctor had had to give me whiskey: “If you take that from me I’ll go stark raving mad!” He said, “Let her have it. She must have something for the pain—either dope or liquor. The liquor won’t kill her.”

It was ten days before Winchell had the scoop, just a line— “What playboy broke Lillian Roth’s jaw?” It was sufficient. My name was splashed over all the newspapers. Lillian Roth, the playgirl, beaten up at a wild party. With my wired jaw I got on the phone and painfully tried to reach Walter in Florida, to tell him this was no playboy-playgirl episode.

Katie was with me now, heartbroken. “Lilly, what are you doing with your life!” My father flew in from Boston. “Baby, you’re messing yourself all up! If I get my hands on that bastard—” My sister Ann lamented, “Oh, Lillian, you’re getting to be a girl people talk about.”

I returned to my hotel and waited. Orchids arrived— from Mark. Then a telephone call from him. He had gone to Washington, D. C, on urgent business. A few days later, another call: against a background of Hawaiian music, he wept tears of self-reproach over the telephone. I hung up and hired detectives to find him. They searched for several days. Then I remembered the Hawaiian music. Mark’s attorney lived at the Belmont Plaza hotel, which featured a Hawaiian band in its bar.

Accompanied by two detectives, I waited in the lobby of the hotel, on the chance that Mark would come there. I was right. He walked in and I pointed: “That’s him,” I said. The detectives arrested him. Jailed on a charge of assault, Mark was out next day on $1500 bail. That afternoon his attorney pleaded with me. If Mark’s disgrace became known, Sonny would be expelled from school. Mark himself was prostrate: if I would only see him so he could ask my forgiveness….

“All right,” I said, wearily. “I’ll see him.”

Carrying a box of roses, his eyes red-rimmed, Mark visited me. “I didn’t mean it, Mommy, I swear to God I didn’t.” He began to cry. “You know I wouldn’t hurt you intentionally. I don’t know what comes over me when I’m drinking. My God, how many fighters have been hit, over and over again, and never a broken jaw! I didn’t know what I was doing. I blacked out….”

So he went on. Why would he do it when he adored me, when his son wanted me for his mother?

I wished desperately to believe him. Was it impossible for me to get along with anyone? And why should Mark set out to harm me? I had been good to him. Thus I reasoned. And having pleaded his case well, he disappeared again.

My lawyer asked for a closed court session when the assault case came up, on the theory that it had embarrassing boudoir overtones. I was assured that his request had been granted. But when I arrived the day of the trial, I learned that it was to be an open hearing before three justices.

I was furious, and the bourbon I had taken to fortify me for my ordeal did little to help. “You’re not going to disgrace me!” I shouted at the judges. “I refuse to testify in front of all these people.”

I began to walk out. A court attendant seized my arm and deftly brought me around until I was in front of the bench again. “You’re supposed to protect innocent women,” I stormed. “Is this the way you do it? I know what goes on behind those black robes!”

The presiding justice snapped:

“That’s insolence. You say any more and I’ll hold you in contempt. Sit down.”

I sat down. My attorney pleaded for a private hearing. The court refused. Instead, the case was postponed. The presiding justice gave me a parting lecture:

“I would probably send you to jail for your unwarranted outburst, Miss Roth, if I did not take into consideration that you are a very nervous, high-strung person and temporarily out of your mind.”

I thought, it’s as good a diagnosis as any.

The case dragged on for months. I stubbornly persisted in my inability, brought on by fear of newspaper headlines, to remember that Mark came to my apartment and broke my jaw. If it had happened on a street corner, there would have been no difficulties.

Ultimately the charges were dropped, and I went to Chicago to work. The club wasn’t as nice as other places I had known, but I felt I had to keep going, if only to forget everything that had to do with Mark. I couldn’t forget, however, because the publicity preceded me, and brought out the curiosity seekers. Some nightclub reviewers described me as “Lillian Roth, formerly of “The Vagabond King,’ now of the drama, ‘She Who Got Socked.’”

I was going downgrade. I had gained weight. I acted like a lush, and I looked like a drunk, and my comings and goings in public places were marked by nudgings and whisperings.

Mark came on from New York, ostensibly to see Sonny, who during the trial had been sent to live with an uncle in Chicago. He dropped in to see me at the club one night. Again, he was the persuasive wooer. Could I never forget one unfortunate, drunken blow? “Can you throw away the rest of your life, and my life, because of one blow? I love you, Mommy,” he said. “I adore you. You know it.”

I was sick, I was heartbroken, I was ashamed, I was alone. Who offered me more? “All right, Mark,” I said “Let’s try.”

He was insanely jealous. One evening when he found me chatting and laughing with a patron of the club, he threatened my life. He made an ugly scene. On another occasion he lunged at me. “Don’t you fool around with anyone else,” he roared.

On closing night I called my personal maid, Elizabeth. “I’m afraid of him,” I told her. “I want to get out of town without his knowledge. Will you help me?”

“Yes, ma’am. I’ll go home and pack for you.”

“We can’t go to a hotel He’ll find us.”

“Don’t you worry, Miss Lillian,” she said. “Safest place is with my family. My father’s a preacher and my mother’s a school teacher. You come with me tonight.” She took me to spend the night in her home in Chicago’s Harlem. To think this was my only haven: thank God, I thought, for these sweet colored people. He’d never dream of looking for me here. For the first time in years I felt like a child cared for by tender parents. The apartment boasted two large beds, one in the kitchen, the other in the bedroom. Her father said, “You’ll feel better in the kitchen bed because it’s more homelike.” And there I slept.

In the morning I had to have my drink, and they managed to make me eat some breakfast What now? Where could I hide? We devised our plan. Lita Gray Chaplin, my good friend, lived in Balboa, California. Elizabeth and her husband would drive me there, and take care of me until I got hold of myself. I wired Lita, and sent Elizabeth to my hotel to gather up my things.

She had packed half my clothes when Mark, who apparently had been searching for me, strode through the open door.

He ripped one bag out of her hands and began pummeling her. “You get nothing from me,” she shouted, holding grimly to my overnight bag and striking back with her other hand. “Miss Lillian’s afraid to call the police but I got nothing to lose.”

When she arrived, she reported: “He begged me to tell you he loves you, but, ma’am, I wouldn’t believe his sweet talk.”

We left the next day. I lay in the back of my car, a big Cadillac, and guzzled liquor. The 2,000-mile trip itself is a blurred memory in which the dominant recollection is that of constant nausea and illness. Once I insisted upon driving: I drove the car into a ditch. By the time police arrived, Elizabeth’s husband had put me in the back seat and was at the wheel. “Lie quiet,” he warned me. “I’ll tell them I was driving.” Another time I became so violent in my self-disgust that I pushed open the back door and was almost sucked out before Elizabeth managed to pull me, screaming, back to safety. They placed me between them in the front seat and never left me out of their sight until we reached Balboa.

Lita paled when she saw me. “Lillian!” she exclaimed, horrified, “we’ve got to put you to bed!” They carried me into her house and her physician cared for me. I collapsed completely. Years later she told me she was almost shocked dumb by my appearance. My face was purple, my eyes all but lost in the midst of two ghastly white circles, my cheeks were networks of broken blood vessels, I was more than twenty pounds overweight, my stomach was swollen from lack of food. I suffered something akin to beriberi. After all, I had lived on liquor during the entire trip.

When I began to recuperate, Lita rented a little house for me on the island, and Elizabeth and her husband remained to take care of me.

Ten days later I was brooding over a scotch in my living room when a sound made me look up. My heart almost stopped.

There was Mark walking soberly in the doorway, and there was Sonny, running to me, throwing his arms around me and crying, “Mommy!”

“How are you, Mommy?” said Mark gently, bending down and kissing me on the cheek.

My mind formed the words, “Oh God, what’s the use!” I could not fight it anymore. I had been buffeted about too much. Sonny sat on my lap, prattling away, and Mark was on his knees, his arms around me, saying brokenly, “I don’t know, Mommy, I don’t know, believe me when we’re married it will be different. We need you, darling, we both need you more than we know ourselves.”

He had found me simply enough. I hadn’t packed the brace I had worn on my teeth at night after Mark broke my jaw. He found it, concluded rightly that I would wire my dentist to forward another, and so learned where I had fled.

Whether because of my weakened condition, or my liquor-fogged brain, or the conviction that it was fated to be, I do not know—but Mark and I went before a judge, and we were married.

The reporters and photographers came en masse to the apartment we rented in Beverly Hills. Pictures were taken: Mark, sweet and protective, sitting with his arm around me, Sonny playing happily at our feet. The headline writers made a day of it. “LOVE LAUGHS AT BROKEN JAW;” “LILLIAN ROTH SOCK LEADS TO ALTAR;” “LILLIAN ROTH WEDS JAW-BUSTER.”

That afternoon several men came to talk business with Mark. He took me aside. “Mommy, have you about $20,000 that we can get right away?”

I said no. All I had now were my policies and bonds.

“Well, Mommy, you want us to start off right, don’t you? These men have a terrific deal.” He explained that he could buy into Joan Blondell Cosmetics, a legitimate business to which Miss Blondell had loaned her name, if he could raise $20,000.

Next day I went out and borrowed the money on my policies.

Sonny became the focus of my life. He came to me one day and spoke with an earnestness that tore at my heart. “Was my mother a bad mother like my daddy says?” I put my arms around him and kissed him. “Your daddy must have made a mistake,” I said. “He wasn’t feeling good when he told you that I saw pictures of your mother. She had blonde hair and blue eyes like you, and she’s watching you now and she’s so glad you have someone to take care of you.” I added: “She’s really your mother. I’m just Mommy. But let’s not tell daddy anything about this.”

We had wonderful afternoons together. It was great fun to bring him games and books, and to take him to the movies. Perhaps, I thought, this little boy will make something of my life. Maybe through him I will become a different woman, and Mark a different man.

My only solace was Sonny—and liquor. There was always a bottle in my medicine cabinet and under my mattress. I tried not to let Sonny see me drink. But I had to have liquor to stop my screaming nerves, my exploding brain, to dull the knifelike certainty that I was going nowhere, doing nothing, living as a shadow in an empty world.

I never fooled Sonny. For when he would find me in one of my nervous fits, or weeping, he would say. “Don’t you need some of Daddy’s medicine?”

Nothing changed. Mark was charming one moment, brutal the next. When he was drunk, he beat me, often in Sonny’s presence. The humiliation of being whipped in front of the child caused almost as much pain as the actual beating. He would pour a drink for himself, then one for me. “Want it?” he’d say. When I put out my hand, he would fling the contents in my face.

He asked for money. “Mommy,” he would say, “we need $5,000 more.” “But, Mark, I just cashed in a bond last week,” I would protest. “I thought that was all you needed. I’m going into my life insurance now.”

“All right, baby, let’s forget it,” he would say. “How about a couple of drinks?” We began to drink—drinks I didn’t need. When I was all but passed out, he would say, “Oh, Mommy, there’s something I forgot. Here’s some papers to sign.”

Even in my blurred state I knew what was happening. I thought, he’s quiet now, and easy, but if I say no…You better sign it, I would tell myself, or you’ll get what you got last time when he went into one of those maniacal rages and took Sonny from you.

He had grabbed Sonny and vanished with him for two days. When he returned, the child was trembling with fear.

I thought, “Oh, God, all right,” and signed. Later I learned I had signed away my insurance policies to strangers whom Mark had made my beneficiaries in return for cash.

One night we had a ringside table with Lita Chaplin and her husband, Arthur Day, at Grace Hayes’ Lodge. The floor show started just as the waiter was serving our dinner. The entertainers were Peter Lind Hayes and his wife, Mary Healy. In show business it’s customary to refrain from eating while a fellow performer is on.

“Eat,” said Mark, when I made no move toward my food. He grabbed my wrist.

“Sh-sh-sh—I want to hear them,” I said. “Professional courtesy.” He’ll be all right, I thought. He won’t dare cause a scene, not with Lita and Arthur sitting there. “I’ll eat in a little while,” I said.

“Listen, Bum,” he shouted, “if you don’t have that plate empty by the time I count ten it’s going into your face!”

I laughed nervously and took one bite, and turned my face to the stage again. Suddenly I felt the blow of the plate in my face—food splattered over me and slid into my lap. The plate had hit me on the bridge of the nose. Blood gushed forth. Waiters came running and the table overturned as Lita’s husband rose and grabbed Mark. I found myself running outside, and then I was in a cab, headed for home, the blood thudding at my temples.

I had no key. There was nothing to do but wait in the hallway until Mark came home. He found me sitting on the floor, propped against the door of the apartment.

He jerked me to my feet “Come on,” he said roughly. “We’re going nightclubbing.”

I stared dazedly at him. “The way I look?” I faltered.

“The way you look,” he said. “Let ‘m all see what a bum I’ve got to live with.”

With my blood-spattered dress, my lacerated face, my dishevelled hair, he forced me to accompany him to one club, then another. People saw me, and gasped. I was like an automaton, without will,

without hope. Here you are, I thought dully, once famous, now infamous, living with a paranoiac. You can’t go lower.

The day came when he beat Sonny in my presence. What I could not do for myself, I found courage to do for Sonny. I packed a bag and took him with me to a neighboring hotel. “Please,” I begged the night clerk, slipping a $10 bill into his hand, “don’t let Mr. Harris know we are here. We must get some sleep. My little boy is a nervous wreck.”

During the night a bellboy rang. “Your husband is coming up the service stairs.” Mark had found me by bribing the night clerk who had taken my money and, as I learned later, considered me a hopeless drunk.

I raced with Sonny down another flight of stairs and took a cab to a second hotel. There at eleven a.m. Mark’s lawyer reached me. “I’m afraid you’ll have to bring the boy back. Otherwise, your husband will swear out a warrant for kidnapping.”

“Promise you’ll be there so he won’t touch us,” I begged. I need not worry, he said. Twenty minutes later I entered my apartment, Sonny clutching my hand. A case of liquor had been opened and bottles were strewn about. Mark, waiting for me, had been entertaining two men. The lawyer wasn’t there.

He jumped up, swept Sonny off the floor and all but tossed him into the bedroom. Then he began shaking me, roaring at the others, “Get out, I’ll take care of this bitch, stealing my son!” I screamed at the men, “Don’t go—” but the door was already closing behind them. In the bedroom Sonny whimpered, “Don’t hurt her, Daddy, she was only taking care of me.”

I tried to make the door but Mark was quicker. He kicked it shut and began punching me, slapping my face with his open hand, muttering hoarsely, “Make a fool out of me, will you—” I pulled loose and rushed into the bathroom, cowering against the stall shower. He leaped at me, pulled me back, then hurled me against the shower. I slid into it. He loomed over me, grabbed me by both shoulders and jerked me up sharply—the shower handle split open the top of my head.

I'll Cry Tomorrrow

I'll Cry Tomorrrow