- Home

- Roth, Lillian;

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Page 10

I'll Cry Tomorrrow Read online

Page 10

When I walked into the judge’s court to say goodbye, he called me up on the bench beside him. “I’m going to California,” I said without preface. He laughed. “I don’t believe it”

I swallowed my pride. “Ben, I don’t have to go. You could keep me here. But once I leave, you’ll never see me again.”

He ruffled some papers in front of him. “I don’t like to make decisions for you,” he said noncommittally. “Shall I see you to the train?”

“No,” I snapped. “Someone else is seeing me off.” I almost ran from the courtroom.

That night Fred Keating kissed me goodbye, and I was enroute to Hollywood. Almost upon arrival, I was cast With Barbara Stanwyck in “Ladies They Talk About” In it I sang, “If I Could Be With You One Hour Tonight.”

Liquor, I thought, was no problem at this time. I could take it or leave it. Mostly I took it—though not while the picture was shooting. I drank to forget. The judge had ruined everything. Why hadn’t I stayed with Willie, sweet, likable Willie? Or gone along with fun-loving Fred? Why was I out here alone? It helped little that the judge wrote every few days. Like his telephone calls, his letters asked nothing and promised nothing.

The men with whom I now went out in Hollywood were interested only in one-night romances. I drank heavily. Frequently I blacked out, waking foggily at four or five in the morning, with no memory of what had happened. That frightened me. Where was all this leading to?

Warner Brothers, seeing the rushes of “Ladies They Talk About,” promptly offered me a three-year contract at $1,500 a week. I spent several days in agonized indecision; and then, fortified with bourbon one night, I telephoned the judge.

“Hiya, Judgie,” I greeted his voice, gaily. “There’s a decision I want you to make—in my favor.”

“What a nice surprise,” he said, and his voice was cool over the wire. “But you shouldn’t be spending your money on long-distance calls.”

“Listen, Ben,” I rushed the words. “Warner’s are ready to give me a three-year contract. If I take it, I stay out here. I’ve been getting your ‘Dear Lillian-Sincerely, Ben’ letters. I really don’t know what to think anymore. Ben—do you want me or don’t you want me? You must make up your mind.”

There was silence at the other end. Then: “I’ll take a couple of weeks off at Christmas and come out there and we’ll talk about it,” he said.

When I hung up, I knew I had to settle this. I took another drink, packed my bags, flew to New York, and telephoned Ben. I was in New York, I told him. I would be over immediately. His apartment was fifty blocks from my hotel, and a snowstorm raged, but I walked the entire distance, the snowflakes melting on my burning face, before I trusted myself to speak to him. I had gotten a divorce for that man: he was going to marry me, I vowed.

When I entered his apartment, Joe Shalleck was there, too.

“Hello, Ben,” I said. “I see you have your legal counsel with you. When do we set the date, boys?”

Ben carefully lit his cigar. Joe spoke: “Yes, Ben, why don’t you name the day?”

“All right, John Alden,” I snapped. “Let Ben speak for himself. He’s pretty good, when he tries.”

There was a silence. Ben drew pensively at his cigar. “Well, I don’t know,” he said finally. He looked at me, and his voice took on a judicial tone, as though he were summarizing a case. “You’re certainly not the most beautiful girl in the world. You’re certainly not the most brilliant But there’s something about you—maybe the way you crinkle your nose—or maybe I love you when you’re angry—but you set the date.”

“As far as I’m concerned, we can be married tomorrow,” I said.

Joe spoke up again. “I’ll order the invitations,” he said. “The wedding’s on me.”

It was set for January 29, 1933.

The newspapers treated our nuptials with the dignity befitting a judge’s wife-to-be. Wrote the New York Sun, on December 13, 1932: “The engagement of Miss Lillian Roth, stage and screen actress, and Municipal Court Justice Benjamin Shalleck, will be formally announced by her mother, Mrs. Catherine Roth, tonight at a birthday party at the jurist’s apartment, 444 Central Park West, when the thirty-fifth anniversary of Justice Shalleck’s birth and Miss Roth’s twenty-second will be celebrated.

“The wedding will take place in January. Miss Roth will give up the stage and make her final public appearance at the Broadway Theatre on Sunday night for the James J. Hines Christmas Fund, the proceeds to go to buy Christmas dinners for the poor …”

“You understand,” Ben had said, “you’ll have to forget your career.” I knew that I wanted a normal life. I didn’t like myself in California. I didn’t like the kind of men who took me out, nor the drinking, nor the blackouts. What had Paul Bern told me when I first arrived in Hollywood, Stardust dazzling my eyes? The men in my life would make or break me.

Without misgivings I gave up my career at high tide. M-G-M phoned me from Hollywood. Paramount wanted me for an important part. Warner’s offered to co-star me with Loretta Young in “She Couldn’t Say No.”

To them all, I could—and did—say no.

The elaborate wedding reception at the Savoy Plaza was at four, the ceremony at nine, the train for Florida left at ten. Mother was tearful but happy, my father drank toasts to everyone. I was gay over repeated goblets of champagne. The guest list of 1,000 was a rollcall of stage and political personalities: Jimmy Hines, New York Democratic leader, Judge and Mrs. Samuel Rosen-man, Justice John J. Sullivan, Basil O’Connor, former law-partner of President-elect Roosevelt, Benny Leonard, Father Thomas O’Neil, Mr. and Mrs. Jesse Lasky, George White, Earl Carroll, Abe Lyman and many more. Ben stood up and read telegrams as they poured in. One he read before he realized it was addressed to Miss Lillian Roth. It said, “Better luck next time.” It was signed, “Fred Keating.”

When Ben and I left, Dad was asleep in a chair in the lobby. I bent over and kissed him. He lifted one eyelid. “Take care of my baby,” he mumbled, and fell asleep again.

The moment Ben and I were alone in our drawing room, butterflies struck my stomach. I was locked in. It was as it had been with Willie, all over again. Now what have I done? Why did I pursue this? I don’t love him….

Desperately I wanted a drink. “Isn’t there any more champagne?” I asked Ben. “You won’t need it, darling,” he said, as he pulled me to him.

After he fell asleep, I lay awake as the train sped through the night, listening to the long, haunting whistle at the crossings, staring out the window at the stars. The moon rode high and clear; the nearest stars were all but invisible. But farther up the sky, they shone large and bright. Was it true that each person who dies has a star to look out from? Was David looking down at me, and what was he thinking?

Our second night in Miami the judge heard me rummaging in my trunk. He came into the bedroom. “I’ve been looking everywhere for some papers,” he remarked. “Do you suppose your mother packed them in your trunk by mistake?”

“I don’t think so, Ben,” I said hurriedly. “I’m sure she didn’t.

“Let me look.” He searched my trunk and in each drawer he found a quart of liquor hidden under the lingerie.

“What have you all this for?” he asked in astonishment.

“Well,” I said nervously, “I thought-well-I thought we might give some parties here—”

“Oh, Lillian! You know liquor is available here.”

I tried to make clear that I wasn’t going to drink the liquor, I just had to know that it was there.

“Why do you have to know it’s there?” he asked.

“I don’t know, Ben!” I said wildly. “Let me alone. I just have to know it’s there!”

Many friends from show business were in Miami that week—Sid Skolsky, Jack Benny, Walter Winchell—but it was a stormy week for Ben and me, with tears and arguments over my drinking. We went on to Havana, where I fell in love with Presidentes, cocktails heavily laced with absinthe. I passed out several times: a

bsinthe was powerful, but it wasn’t going to beat me. I drank more Presidentes, and lay most of the day in a stupor on the beach.

In the train back to New York, Ben asked, “Is this the way our married life is going to be, Lillian? Are you just going to continue to drink?”

“I don’t do anything wrong, Ben,” I replied miserably. “And I’m really not drinking so much. Don’t I really behave all right? But if it worries you, I promise it’ll] be different when we get back.” I would be a real judge’s wife to him, I vowed: “We’ll have a beautiful home and maybe we can have a baby right away.”

Our apartment—with an extra bedroom for the baby we hoped to have—overlooked a magnificent vista of Central Park, with its blue lake gleaming like a jewel in a green setting. I indulged in a spree of decorating, and I was proud to think that I was one of the first in New York to use bold white and black: white walls, black velvet couches, zebra-striped pillows, white leather seats, a modern bedroom with spun-glass walls. I had everything a woman could want: youth, position, a handsome, respected husband, and I was financially independent-money I had earned, a bank account of more than a quarter of a million dollars. What more could I desire?

“Why not,” I suggested to Ben some weeks later, “why not have open house once a week? I love to watch people have fun and I want to help you politically.”

Thus began the tradition of the Shallecks’ Saturday night parties. They were successful from the start. Besides Mother and Ann, our steady guests included many who had been at our wedding, as well as such friends as Georgie Jessel, Lita Gray Chaplin, Milton Berle and Nino Martini.

Ben was delighted after the first party. “You were a wonderful hostess, darling,” he said. “I was proud of you. You hardly drank.”

“Of course not, Ben,” I said, and I believed it. “When I have exciting things to do, I never think of a drink.”

He was unaware that I had fortified myself before the guests arrived. “You know, Lillian can’t drink much,” he commented one night. “She takes one drink and it lasts her all night. Look at her, bouncing around full of energy.” He could not know that as I made the drinks in the kitchen, I sampled them; or that long after the last guest had left, the maid and I began our own drinking party as we emptied ashtrays and cleaned up…while Ben slept the sleep of the innocent.

Ben could not know how I dreaded going to sleep. Strange memories and fears assailed me. David had died paralyzed and blind. My father had been virtually paralyzed that night as he sat in a drunken stupor after beating Katie. I had lain paralyzed when the old man with the cigar painted me, so long ago. So many nights, lying next to Ben, I closed my eyes and thought I slept, yet strangely, I was awake…I must be awake because I could look across the room and see the dressing table with my perfumes on it. I could see the chair opposite our bed—first its legs, then the judge’s shoes and socks, then his trousers neatly placed across the chair, then his shirt and jacket carefully placed above the trousers—all precisely, meticulously laid out, ready for the next day. “All that’s missing is his gavel,” I thought, and giggled. Or was I giggling? Was I awake? I couldn’t move. Invisible chains bound me. I tried to scream, but no sound came. My throat was locked. Now I’m screaming but he doesn’t hear me. Easy, easy…this will pass. You’ll have it again, but it will pass.…Then, unexpectedly, I could move. I would get out of bed, my heart thumping madly, my body soaked in perspiration, and with a shaking hand pour myself a drink, and then another, and then another, from the bottle I now had hidden in the clothes hamper in the bathroom. Then I could go to sleep and the paralyzed dream, the screaming trapped helplessness, would not come again.

When a woman wants a child and cannot have it, her yearning can become an obsession. Motherhood, I thought, would bring me the peace I sought. It would dull that indefinable ache, the loneliness that was my other self, the something I wanted I knew not what Perhaps I would find contentment if I had a child of my own upon whom I could pour the love locked in my heart, the love I could give to no man save David and his memory.

In vain Ben and I consulted physicians. No babies came. Had the child been a boy, his name would have been Charles; a girl, Anna-both named for Ben’s father and mother. We had it all arranged. In the end, I resigned myself to being childless.

Yet I had to keep busy. Perhaps mothering other people’s children was the answer. Soon I was taking a score of orphans to my home of an afternoon, arranging little parties, serving ice cream and cake, and surprising them with little gifts. I took them on auto trips to the zoo and sometimes to the circus.

With Molly Minsky, wife of the burlesque impresario, I founded a philanthropic organization, the Charlanna League, named for the children I could not have, to raise funds for the Second Street Day Nursery. I held luncheons and cocktail parties which sometimes began at three p.m. and lasted through midnight There was a kitty on the bar; at the end of the party I found many $50 and $100 bills.

Others in our group were Mrs. Berle and her daughter Rosalind, Lita Chaplin, Mitzi Green and her mother, Florence Lustig and Ruth Bernstein, old friends, and Ben’s sister, Estelle Milgrim. We held bazaars and ram-mage sales, and raised considerable amounts of money. A glass of beer kept me amiable for hours at the sales. After I came home, however, I had to take several straight drinks, and even a stronger nightcap to ward off my fearsome dreams.

In the few years my League was in existence, I resigned three times. Some new members resented the strict parliamentary rules I insisted upon at meetings. (Ben had taught me this.) I was high-handed, they complained. Perhaps I was. I worked hard, and never failed to fortify myself before a meeting.

What particularly incensed me was the charge that I engaged in charity work for publicity. At one meeting I announced:

“I’ve been glorified internationally and I don’t need the glory of a hundred women. If you think I’m doing this for personal publicity, I’m resigning. I’ll do my own charity work.”

High-handed or not, apparently I could raise money, and each time a resolution was passed to invite me back. The final straw came during a particularly cold February when nearly all the members were wintering in Florida. I called a meeting of the handful in New York and we voted $1,000 from the treasury to buy shoes and snow-suits for needy youngsters.

When the sojourning members returned, they put me on the carpet. “These children managed to live all these years without you,” one woman snapped. “You had no right to spend this money when we were away.”

I was too hurt to answer. I resigned for good, and went home. Couldn’t I get along with anyone? Couldn’t anything work out right for me?

Although beer by day and liquor by night satisfied me while I was busy in the Charlanna League, now my nerves demanded more. I switched from a morning beer to a jigger of liquor first thing after I awoke.

It seemed a good formula. I improved upon it by pouring two ounces of bourbon into my breakfast orange juice, so the judge was none the wiser. One afternoon I was shopping at Saks-Fifth Avenue with Ruth Bernstein. I stood examining charm bracelets at the counter, when the store began to spin. Sweat streamed from my forehead and splashed in large drops on the counter before me. My knees began to buckle. I couldn’t swallow.

I clutched Ruth. “Get me outside.”

I leaned against the storefront and the cold air revived me. I caught my breath. “Oh” I said. “But that was a bad moment. Must be something I ate.” We continued shopping. A few minutes later, while Ruth was trying on a hat in another store, it happened again.

She managed to steer me outside, where the people and the traffic and the noise of the avenue rushed headlong at me. She hailed a cab and opened the windows. “Should I take you to a doctor?” she asked anxiously.

“No—I can’t swallow—get me water, quick!” I gasped.

The knowing cabbie, who overheard us, stopped before a bar. The bartender took one glance at me.

“Water, hell,” he exclaimed. “She needs a drink,” He

poured out a tumbler of rye. “Here, get this down, Miss.” 1 reached for the glass. My hand shook so violently the liquor spilled. Ruth held the glass to my lips.

The bartender watched me. “These spells come often?” he asked casually. I shook my head. “Take a tip, Miss,” he said, “carry a shot or two with you in the future.”

I realized that I could never go out of the house again without liquor. Orange juice and bourbon in the morning was not enough. The physical demand was growing. I would need liquor more often—not because I wanted it, but because my nerves required it. Since I was a judge’s wife, I couldn’t be seen dropping into bars: I must carry my own liquor. That day I bought small two-ounce medicine bottles in the drug store, filled them with liquor, and thereafter was never without a couple in my purse.

Soon I was slipping down doorways, vanishing into ladies’ rooms, anywhere I could gain privacy, to take a swift drink to ward off the spells that came upon me with increasing frequency. The two-ounce bottles graduated to six-ounce, and then to a pint, and in the last years of my marriage to the judge, wherever I went, I carried a fifth of liquor in my bag.

“Lilly, darling, aren’t you drinking too much?” my mother worriedly asked one day. Neither she nor Ben had any idea of how much I consumed daily; but they knew of my nervous spells.

“Oh, Mom, I can stop when I want to,” I said irritably. “When I have work to do, don’t I do it? When I have to run a charity affair, don’t I handle it well? Don’t I behave all right in public?”

Once, driving down Tenth Avenue with my sister-in-law, Estelle, I said, “I don’t know why I’m so unhappy. I have everything in the world. And yet…Estelle,” I said somberly, “I see myself very poor someday. I see myself deserted. Something awful is going to happen to me. I’m going to be penniless and my great fear is, what will I do? And what will happen to my mother?”

“How can you cry carrying cake in both arms?” she said, marvelling.

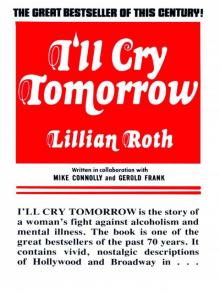

I'll Cry Tomorrrow

I'll Cry Tomorrrow